Silence

The Grand Watch Speeder Upper

I’m a Deist. You’re never supposed to discuss religion or politics, but I’m only discussing religion. I’m a Deist. It is the religion of the forefathers, and since we know that everything they did is great, it is great.

If you don’t know, it’s the Grand Watchmaker theory, that God created the universe, and just stood back and let it unfold. I used to be an atheist (as many of you are), but then popcorn and whipped cream. Come on, there has to be a divine intelligence behind the fact that cow fat can be made, artificially, into the most delicious substance ever. When you add caramel, which is burnt sugar, it makes creme de divine intelligence de Brest.

And puppies, and consciousness, and love and all that. Fine.

Silence, a three hour movie I saw largely because how could I not see a movie about 17C monks in Japan, works. It shouldn’t, but it does. I suspect a large part of that my liking it may be due being a Deist. Being religious in this case is very much like liking Ms. Sherilyn Fenn. If you like Ms. Fenn, you’re going to like Three of Hearts. Religion is a hot girl from the 90s.

Most of the people who read this, because I know them personally, are atheists. They don’t like Sherilyn Fenn, which is about as dirty a rhetorical trick as I can muster. Who doesn’t like Sherilyn Fenn????? Heathen!!!!

But you might, nevertheless, like Silence. I think it’s Mr. Martin Scorsese’s most compelling film since Casino, by leaps and bounds, in fact. Throughout I kept fantasizing that his next film should be straight up horror, but I soon realized that Silence was in fact that: a terrifying version of Hostel.

And if it’s scary, let us praise the fact that it has a very straightforward setup. As the two priests set out to find their own mentor (goal one, Kurtz), they risk being killed (danger one), or renouncing their faith (danger two). This is easy to show on screen, and absolutely consistent with the characters – Mr. Liam Neeson’s eternal soul is something that they want to save, and we want them to.

The film has a kind of time compression worthy of Doctor Who. If the universe has balance, this is where the time that made Arrival four hours long went.

The film, despite being one of the most esoteric subjects of any film with a budget over a hundred bucks, is basic, in the best way, screenwriting. As the priests go outside in daylight from their hidey hole for some sun (up, with inevitable discovery), they are discovered (down), and called on to come out without the secret code (fear), they go out, and discover more Japanese Christians (up), taken to another Christian village (too far up, leading us to know something bad is coming fast). This is in the space of five minutes.

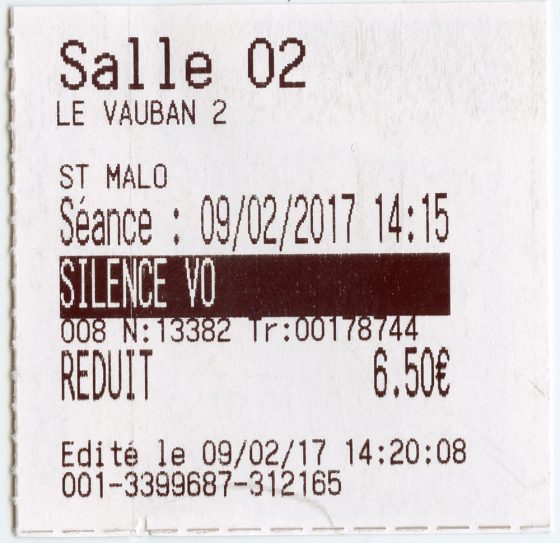

Can’t say I saw the film since I missed the first three minutes, because Le Vauban 2 doesn’t have trailers. I love them.

What I’m trying to convey is a note that I so rarely take: ‘I’m not bored.’, which is followed by, to indicate its rarity: ‘I’M NOT BORED!!!!!!!!’. As the film comes to the end with a Dutch trader telling us the fate of the Priests, there is genuine confusion and clock checking – but it’s only been ninety minutes. We can’t be done yet. Nope, it’s been 160, a kind of time compression worthy of Doctor Who. If the universe has balance, this is where the time that made Arrival four hours long went.

For those of us ignoring the rule to discuss religion, let’s not discuss it for another moment. The film is a genuine scopophiliac’s delight as we imagine more time lost – the days spent drinking and telling stories until the light was just so. For those of you inclined to the divine, Issei Ogata-tono gives the performance of the year, and that includes Mr. Casey Affleck, who was great until this guy showed up. You cannot take your eyes off him. He pulls off a full kabuki sigh, letting his body drop in an obvious and dramatic resignation, yet in an embodied way that would make Mr. Sanford Meisner…uh…give a very small but telling eyebrow raise. It’s something else.

At the end of the sermon, we get to the sermon. I’d hard pressed to think of a more sophisticated take on one’s relationship with God. The film doesn’t wallpaper over God’s relationship to colonialism; the Buddhists give as good as they get, and this is meant in a very literal sense. Besides and in somehow in contrast to the argument presented by one character that Buddhists seek to find the divine within, they also engage in the kind of real sadism that horror film makers generally eschew.

The multiplicity of legitimate points of view makes the film less like the inconsistency we’re used to seeing as excuses for characters, and more like an engaging argument one would have in one’s head. Though coda of the film makes the rather unfortunate mis-step of dedicating itself to the lives lost in the religious purges of the era (just as I have made my own in trivializing it), before that moment, it uses the historical background for its own devices. And the history would have been interesting enough.

The silence to which the film refers initial is God’s silence, given all the horror that Mr. Andrew Garfield witnesses: where is God when man causes so much suffering? This is transformed into the silence that one can have with God, that, by the end, proselytizing is no longer a requirement of faith. As a Diest, I’m required to love this, but I think anyone would, especially at this point: if your religion is so great, how come you gotta talk about it so much?

Hey, that’s me!

The Take

$17.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]