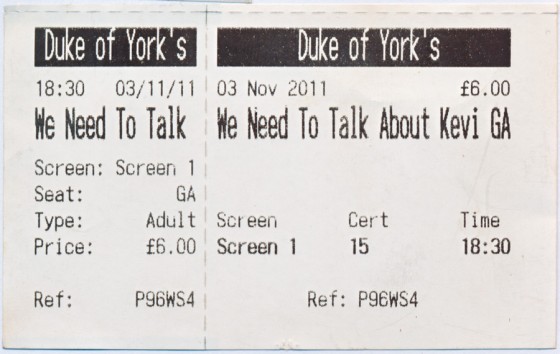

We Need To Talk About Kevin

Unmentionables

At the cancellation of the very fine Prime Suspect (the US version, not the wildly overrated UK version. That’s right, someone finally said it out loud), I wonder what it’s like to make something great and not have anyone notice. Certainly everyone who works in TV knows about this, but I think in particular of all the films, like Vertigo, Blade Runner, Husbands and Wives, Naked Lunch, It’s a Wonderful Life, The Big Lebowski, and even Citizen Kane and how they affected the careers of their various filmmakers. These are, all of them, not great, but exceptional, and were, well, either ignored at the time, or praised and damned by the lightness of it. They were not understood as the genre-defining and recreating films that they were. My theory that the various careers of these filmmakers were sent off course by their masterwork’s reception may be a case of cum hoc ergo propter hoc. This is only natural; when you see the headline Brett Ratner To Helm Red Dragon right next to World Comes To End, what else are you supposed to think?

But whether this is causal or correlative, it can be said that the filmmakers in question began a decline soon after their most complete and personal work, some of whom (Mr. Cronenberg in particular) never recovered. I acknowledge that what with all the money involved, it’s much easier to give the Longbowman’s Salute to the critics if you’re a painter, or some idiot writing a blog. But we do this to be liked, and it hurts bad enough when people don’t like your Legend’s or Topaz’s, but you when you do something amazing, and no one really notices, it’s like when the horrible girlboyfriend breaks up with you. And it leads to the same place: maybe I should just give up, dress schumpy, get some cats and make Hollywood Ending.

It could happen to anyone.

I'm going to Cannes next year to scream at all the idiots. From my extremely expensive hotel balcony. Hey, jury member? What's the gravitational velocity of a 2008 Vauve Clicout from 20 stories? The correct answer is you're dead.

And so I must praise, and praise loudly, Ms. Lynne Ramsey and her, yes, exceptional, We Need To Talk About Kevin. This is a film that played at this years Cannes, and was overlooked for the A-Narcissist-Suddenly-Figuring-Out-He’s-Going-To-Die-Is-The-Same-Thing-As-Insight-At-Least-To-Another-Narcissist’s Tree of Life. But surely best-director, dear jury? No, they reply, because we’re art-types and we’ve never actually seen an action movie (or any of the better films it was based on), let’s award that to the soulless, and confusedly boring Drive. My first reaction to finding this out follows unedited:

‘Re: Cannes, Of course it doesn’t win against The Tree of Life or the shockingly bland Drive. It actually has an emotional impact and competent filmmaking. How can someone make something so astonishing, not get any praise, and keep the hell going? I’m so glad I don’t do this anymore, if the shit they’re praising is Drive. Fuck everybody. I’m going to Cannes next year to scream at all the idiots. From my extremely expensive hotel balcony. Hey, jury member? What’s the gravitational velocity of a 2008 Vauve Clicout from 20 stories? The correct answer is you’re dead.’

I think you’re probably more shocked to find out that what you read here are, in fact, edited, versions of what I write. And that I haven’t the faintest idea how to spell ‘Veuve Clicquot’.

In the first few minutes, how would I have known that WNTTAK would be the best film of the year, and in fact the best in a long time? It begins much like Tower Heist (which I’m fairly certain is a sentence you will read nowhere else). Tower Heist, slight but vague, opens as all movies do: with the money shot. Either crane shot transitioning to helicopter view of the city that runs through the iris of the main character, or overhead zombies turning into the bacterium that infects the zombies and we zoom out to reveal…zombies, pretty much every filmmaker, even the erstwhile Mr. Brett Ratner, thinks about the first few shots of the film. Having gone over the script eight billion times, it’s just the part you know the director has read the most before they got bored, leading them to actually take the trouble to visualize it. The fact that this is typically one or two pages should not discourage us. Unless we’re actually paying money to see movies, of course.

My notes, almost in their entirety: ‘Nice Font’. Never a good sign. Also, possibly a very good sign. Don’t remember if I was ambivalent or indifferent.

And so, the first few minutes of We Need To Talk About Kevin, cut between the red of an unexplained tomato festival, and the red paint thrown on Ms. Tilda Swinton’s home in retaliation for her son’s mass murder (also unexplained). ‘Strong, but can she keep it going?’, or so say my notes. I had been hurt by Brett Ratner before, you see.

Everyone thinks about the first few shots of their film, and Ms. Lynne Ramsey is no exception, only she has thought about the first few shots of her film because she has thought about all of them. Speaking on the visuals alone, there isn’t a single moment of laziness. In fact, given the fact that you get your narrative information in dribs and drabs, her visual skill acts as a kind of CGI, which may be another sentence you won’t read anywhere else. Let me explain:

There’s always going to be boring bits in films; if it was all narrative… okay, once again, that would be great, but in the real film world (as opposed to the real world in film), there are going to be parts where nothing is happening to propel the story forward, as in the title sequence of, I don’t know, anything, where we see the guy parking, turning off the car, checking the parking brake, opening the door, checking the parking brake again, crossing the street and finally exclaiming: ‘Story. There you are’.

In recent years, CGI has taken up the fight against unskilled filmmaking, with the excesses of Mr. James Cameron being the most obvious example: you’re not bored silly audience member, look at the shiny thing over there! And so, like seeing a nanobot climb an eyebrow on the face of Mr. Keanu Reeves as he jumps into the pilot’s seat of nanobot on the face of Ms Charlize Theron, the shots of WNTTAK, bits of eggshell and fingernails, a CD that says ‘I Love You’, a mouth surrounded by cheetos detritus, tomato juice and blood keep you in. It’s like an action film for scopophiliacs; you’re kept in a perpetual state of bliss even if you don’t know what’s going on.

And for the acting junkies (dramaphiliacs?), who are clearly willing to tolerate terrible films whose only credible interest is the performance, there’s Ms. Tilda Swinton. ‘I don’t even think Tilda Swinton could have pulled that off’ is something you might say about another actor, and now I’m saying it about her.

Ms. Swinton has done exceptional and compelling work (post Duplicity and post-post-Bourne, I am convinced this she may be the singular reason that Michael Clayton is the only good movie that Mr. Tony Gilroy will ever make), but she, and the deeply creepy Kevin children, are outstanding here.

Being a fetish based medium (you can’t see what’s beyond the edge of the screen after all), film performance works largely on what’s not shown. The first time we meet Kevin in jail, we only see his mother’s face, and she somehow expresses what we need to see in him. This, without saying a word. Conversely, when it’s revealed, in a devastating moment, What The Bike Locks Are For (I was confused by the critic’s appraisal of this film, as well as their simply missing parts of it entirely. I was supposed to be surprised by this, even though it is revealed early on in a montage. Maybe they were too engrossed in the first two pages of Brett Ratner’s script), Ms. Swinton’s face isn’t even shown. And yes, the Academy Award for Best Actress goes to….the back of Tilda Swinton’s head.

Which leads us, conveniently at least for me, to the story. It may sound like I’m shorting the narrative aspect, but this is equally as skillful, which leads us further to the otherwise inexplicable title of this piece. No, I’m not talking about ladies undergarments or cancer, but the way in which effective narrative lets us as the audience fill in the gaps. Ms. Ramsey’s restraint is remarkable, and it contributes to the story and the experience. The Kevin in question is shown wearing diapers at age 6, and it’s not foregrounded. In any other movie there would be a best friend to explain this, and a response, and over the shoulder shot-reverse shot reaction. Come on; it’s been two pages. I’m bored. It’s a sign of immense confidence in both her ability, and in her audience’s to read it.

Thank you. Thank you very much.

This makes the film not unlike Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (though not at all like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which is great in its own right. If Mr. Kenneth Brannagh went to the gym, we want to see him. Oiled). Hidden beneath the layers of the book is, underneath the captain’s log, beyond Dr. Frankenstein’s self-serving nonsense, is the story of the monster, coming into being. Likewise, Ms. Ramsey very deliberately (in the correct sense of the word) lets us get to the heart of, well, not the story. We know the story, so the heart, I guess. We know what’s going to happen. But we only learn gradually what it’s about.

And so, it’s entirely possible, given what I’ve read of the reviews, that this film may have been unhailed because of the subject matter. Critics have no problem with violence, as evidenced in Drive, which shows violence is real, man, so that we’re like, not encouraging it. So we’ll just let Mr. Eli Roth keep practicing his Nobel Peace Prize speech, and instead praise this film’s restraint once again, as WNTTAK has virtually no onscreen violence. No, I suspect that critics have eschewed this film because it’s about something deeply primal: the fear that all parents have about the utter lack of control over their children. And yes, after 20,000 years of civilization, someone finally said that out loud. What makes this film a success is what dooms it; a worse made film on the same subject would have left room for argument. Instead it captures, perfectly and completely, the mood of being a parent, anxious, loving, ambivalent, totally responsible yet powerless. Whatever its subject, it is a film of absolute singularity, and the way in which the acting, shots, narrative coalesce into its core and clear purpose, this is its masterful accomplishment.

I’m aware of the irony that no one will notice the praise I heap upon a film that no one seemed to notice. It’s possible, no, no, I must accept this, that even Ms. Ramsey may never read this. But I send this post to be absorbed into the electromagnetic ether for two reasons: 1) as you have no doubt gleaned by now, and for reasons unknown to me, I caught the I’m-My-Own-Biggest-Fan bug long ago. No one finds my jokes funnier than I do, and certainly no one finds my insights more insightful. The fact that I’m the one who made them technically means that I can’t find them insightful, but that’s just another example of my insight. If you’re going to beat your head against the wall, this is a disease that you need to protect you from damning praise. Which may make it an antibody. What do I know? I’m a electromagnetic-etherologist, dammit, not a doctor! And so, 2) in, by, via and through my sheer egostity, I fully believe that I can help Ms. Ramsey catch this disease/antibody, if she doesn’t have it already. If not, the crushing disappointment will cause her to accept the reins of Pink Panther 3: The Exact Same Movie In Every Way As Pink Panther 1.

Okay, once again, that would also be pretty great. Have at her, world!

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]