Sinister

Why Quiz Show is a Horror Film

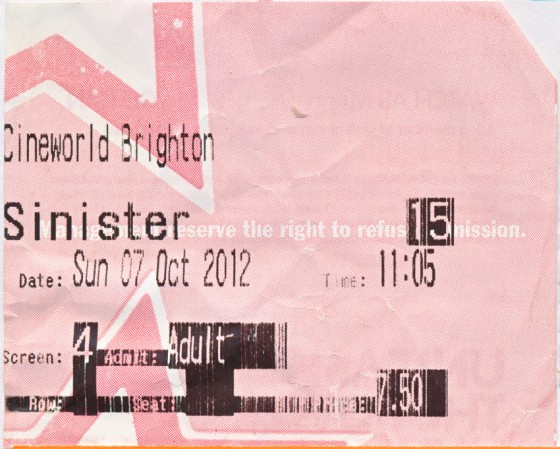

Sinister

20 November 2012 @ The Cineworld Brighton

$7.00 or, if one must be prosiac, and one must...★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆

Sinister is unremarkable, but strangely scary, or at least creepy, or at least foreboding, or at most, scary. Thinking about it afterwards, it remains unimpressive and yet it works. Being the rule obsessed person I am, I am trying to work out why, knowing full well that horror films depend on the suspension of the rational, the places where cops, daylight, physics and even story logic cease to have their power. Fear is the thing that we put away with rules, even if that mean that rules always remind us of the fear. That and going to see horror movies of course.

The correct adjectivized form of dread applies to films without it: they are dreadful, but technically speaking they are dreadless

Yet Sinister was, well, maybe tense is the word I’m looking for, unlike, say, the plot heavy The Awakening or the bafflingly overpraised Pan’s Labyrinth. Why? Was it the ridiculous – read implausible – darkness in a 1960s sun exposed California bungalow? Maybe. Darkness is kinda scary. There’s certainly a very nice opening bit where Mr. Ethan Hawke discovers a single box marked ‘Home Movies’ in an otherwise empty attic. It’s a swell image, and we as the audience know that he shouldn’t go into the attic, shouldn’t open the box, and shouldn’t talk to the people under the stairs, all the while knowing it’s okay from a story point of view that he does (except for the last one, which is from another movie).

Stupidity (and intelligence) is an important aspect of our sympathy for characters. We’re still going to like our hero(ine) if the he or she goes to sleep, or answers the phone, or watches a videotape, because these are normal things to do. But when someone espies a scythe wielding flesh dripper, who explains, quite clearly, ‘My duty to the public safety necessitates that I inform you of of the following: upon your further approach, I intend to dispatch you with the prolonged sadistic glee that the audience not so secretly desires. Nevertheless, come here little girl!’, and, in the case of films like Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, or, as it happens, The People Under The Stairs, she, or they, does. Or do.

Again, great comedy. Not great horror.

And with this box, and what characters do and don’t do, we get closer to why this film works better than it has any right to. Yes, from a plot perspective, Sinister’s got, at best, forty minutes of material. Prolonged scenes of Mr. Hawke et familia wandering in the dark, not looking behind them, walking very, very slowly do not a film make; they are the inverted horror film version of an endless car chase, and just as exciting.

And yet, I think what carries the film forward is actually just one moment at the beginning, where Mr. Hawke chooses. Having found film footage of a family being murdered, he initially calls the police to report the found evidence, and then changes his mind, wanting so desperately to rekindle his true crime writing career. Maybe it’s a stupid choice, but it’s a believable one, and it doesn’t spoil our intelligence sympathy quotient, which is another term I’m going to use a lot. I’m even going to abbreviate it.

What the act of choosing does do is infuse the film with a sense of dread, which is probably the word I was looking for three paragraphs ago, although technically, the correct adjectivized form of dread applies to films without it: War of the Worlds (either one), anything by the uber-hack Lost hydra, all of the Twilight films, requels, premakes, and the trailer-shows-the-first-and-last-ten-seconds-films that we have today.

They are dreadful, but technically speaking, they are dreadless, they lack the resonance that carries us through the events of the film, all the while echoing the characters’ fate. Macbeth, The Killing (1956 – not the anemic and dreadless (see, I invented a new word, and I’m going to use the shit of it) TV series, either the Dutch incarnation, or the I-can’t-believe-it’s–actually-worse-than-the-Dutch American one), A Simple Plan and so on are actually horror films, that the feeling of inevitable doom arises not from a guy wearing pins or talons on his hand, or whatever you’re going to wear for halloween this year, or ironic Halloween ten years from now, but instead from the feeling, as events unspool into chaos, that things wouldn’t be this way, if only he had… It’s the feeling you would get if you were watching me standing in line for What to Expect When You’re Expecting.

Don’t be ridiculous. I don’t have a choice.

The Take

$7.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]