If I wanted to be depressed, I would have seen a comedy

Leaving the stinky Eastbourne Curzon, having seen Calvary, I thought of the many times I had tried to see it, and the travails in doing so. It was a movie, it was playing, and the first time, I didn’t feel like it, and the second, I was a bit sleepy. But given the quality of Mr. McDonagh’s last film, I wanted to go, so I created a fake motivation. Like the Allies prosecuting the Nazis quickly after the war before they could forgive their crimes (doesn’t count as a Nazi metaphor, it’s an ally metaphor), I bought the train ticket to Eastbourne, reasoning that I’d be out the £11.20 if I didn’t go. And here’s something that I almost never say, or I think, or thought, since that’s how we began: I wish I hadn’t.

Not that it’s a bad film, which it isn’t. And it’s certainly trying to be a good one. There’s a great set up where an unseen man explains how he’s going to kill the one good priest because of what a bad priest did, and we wait as the days pass. And there’s some various fun lines and observations along the way, with characters getting increasingly darker as revealed in their confessions. And though it never quite gels as a real situation, or even a felt one, it’s certainly a noble try.

God grant me the serenity to blame someone else for the things I can't change, the courage to blame yet another entity for my lack of serenity, and the wisdom not to look to closely at what I'm doing.

But they kill the dog, so to speak and also literally, inasmuch as an onscreen event can be literal, and it’s all a bit nihilistic. No, relentless. Calvary, which I wanted to like very much, has a kind of ugliness to it that winds up being irredeemable, a fact not aided by three slow-motion shots of Mr. Brendan Gleeson’s brains being blown out. There’s a bit too much satisfaction in the act of nihilism itself, perhaps the appeal.

And it would be ordinary pleasure of my own to spoil it for you, but I just don’t want you to see it. It wants to be complex, and winds up being rather nasty, with the ambiguity of the lead’s daughter visiting the man who killed the priest (he kills him in the end, by the way. Hey, if Mr. McDonagh Peckinpah-ed the shot three times…) possibly there to forgive him. But we should make it ambiguous. Like life!

If you’re going to remake Journal d’un curé de campagne, don’t. No, that’s the whole sentence. I respect the search for grace, and that’s one way to pull this kind of dark wallowing off: with all the sin and doubt in Bresson’s film, there is redemption as well. And without the laziness of ambiguity either. The second way to pull off the darkness of humanity, and I think this is true, is by making a comedy. Arrested Development, if taken on story alone, would make you want to blow Mr. Gleeson’s brains out (and that’s three).

God bless old style tickets, stinky and ripped seats, and extremely stale Belgium chocolate. And He did.

Reading the reviews now, one of which not ungushingly says ‘On the strength of only two films, McDonagh and Gleeson are a director/star team on a par with Ford/Wayne, Fellini/Mastroianni or Scorsese/De Niro’ I discover that I was, unbeknownst to me, watching a comedy, the hyperbole of that last review somehow underscoring. The fact that it’s not really very funny be damned…hyperbolically!

And yet, I feel like someone has to defend the poor dead dog. It’s not just about dog killing, though that would be more than enough. It’s about the desire to do it. As a writer, you are God. This isn’t the world, it’s the world you made, ergo, you wanted this world. When you then proceed to ask, who would want a world like this, it’s not deep, it’s just circular. In this universe, there is a God to blame, Mr. McDonagh, who thinks it’s all arty and interesting to engage in lazy debates about the nature of evil, whereas reality merely contains a bunch of people acting like they know what’s going on when they don’t.

It reminds me of the convenient questions that atheists seem to want to ask of God (what a terrible life, and so short!): It seems, and this film is no exception, that we call to the heavens over some great injustice, it is for something that Man did, aka, Why don’t You stop people from doing wrong? Don’t control me! Everyone wants free will, unless they don’t get what they want, then they want a scapegoat. God grant me the serenity to blame someone else for the things I can’t change, the courage to blame yet another entity for my lack of serenity, and the wisdom not to look to closely at what I’m doing.

Look, if you want to believe there’s no such thing as free will, that’s your choice, and I think I got it, or got why he didn’t get it, when near the end, Mr. Gleeson espies an airplane worker causally leaning on the coffin of a body headed back to France. In this film, it’s representative of the casual disrespect that represents modern sin, and it causes Mr. Gleeson to return, ever so nobly, to his death. And I get this mechanically, like how I get serial killers recreating other serial killers according to the days of the week because they were abused by calendar makers. But it’s a more of an abstract getting it.

And here’s the final problem, that it’s less a moral or philosophical question than a film one. Unless you’re trying to please critics, the best way to tell a sad story is to tell a joke. The tragedy is failing to see the humor, which is also the humanity. Leaning on a coffin and chatting is something that GoB would have done, sure. But it’s also something that Mr. Gleeson’s character would have done in the last and much, much better film, The Guard. There’s nothing sacred about a dead body, but there is something sacred in jokes. And as we see Mr. Donagh taking the same path of Mr. Thomas Anderson of making not fun films anymore, it is a tragic obituary for his career: cut down in the prime of life by the artsy call of tragedy.

The Take: Calvary

-$11.00

Because whatever films are about, it’s mood, the actual feeling that you get watching the damn thing. Some people, evidently, enjoying wallowing in the idea that humanity is irredeemable, and that the one character who doesn’t think so should suffer and die. The new Godzilla is terrible, possibly worse than the 1998 version, but both are preferable to the experience of watching Calvary. Insatiable disgust is generally not a mood to seek out despite movie critics enjoyment of it, and my enjoyment of inventing theirs. Now that I think about it though, Godzilla ’98, has that kind of Hobbesfreude quality that we secretly love, since the human characters are so actively unpleasant, you can only root for the sympathetic lead: Godzilla. I remember watching Godzilla gently nudging one of her young in that film, after the nasty, nasty humans had killed it, and thinking joyfully: kill them all! Maybe I would have enjoyed Calvary in 1998, as it is the same film. Though I guess not, since I would have thought: who rips off Godzilla, and doesn’t even provide you with a brief, yet satisfying ‘Kill them all!’ moment?

And the mood that new Godzilla creates?

Afterwards, I was grinning ear-to-ear for ten minutes. Really. People were staring at me on the street. I’ll admit, I resisted at first, and I confess I’m not sure if this is the Age of Camp or if I have reached it, but the level of absurdity, cliché and situationalism finally pushes you over the top, and you just can’t stop giggling. I’ll try to do it justice to it in a paragraph.

I failed. But it is an enjoyable five hundred and sixty seven paragraphs.

Mlle. Juliette I-can’t-possibly-die-I’m-the-wife-and-it’s-prologue-Ahhhhhhhhh! Binoche, well, dies in a cataclysm that utterly collapses the nuclear power plant that Mr. Bryan Cranston is also in, but doesn’t kill him for some reason. We know it’s the past, because Mr. Cranston has a bad wig. We now cut to fifteen years later (which we know, because Mr. Cranston has a slightly different very bad wig), and a son that is bland for ten minutes. After paying to see a movie titled after a giant radioactive lizard, we will now spend an hour of having people not believe that there’s a giant radioactive lizard. Well, technically fifty minutes. There was that ten minutes of convoluted explanations why the most surveilled time on our planet cannot find a giant radioactive lizard. Also, five seconds not explaining how a truck full of soldiers can just sneak up on Mr. Cranston silently, and, instead of taking him away from the secret base of monster eggs that they’ve been hiding from him the last fifteen years of wig wearing, do what is technically a literal about face and take him, this time, to the very center of the secret base.

Mr. Cranston then gives the obligatory: ‘You have no idea what’s going to happen’ speech that we’ve seen in so many, many times. And it’s vaguely ominous in the trailer. Watching the movie, however, the omninousity is slightly undercut by the fact that the character, at this point in the story, also has no idea what’s going to happen. In fact, the people he’s warning do have a pretty good idea about giant radioactive monsters, so they should be warning him. It’s a very odd moment.

Luckily for knowing what is going to happen, or is happening I suppose, a giant insect monster wakes up, and Mr. Cranston’s exceptionally unremarkable son puts on his gas mask to watch him walk away. There was no reason for him to do it, other than they hadn’t got a shot of the creature walking away through a gas mask. I think this where the film finally took off for me. The lead’s reaction to a giant insect creature? I feel the urge to be wearing a gas mask. Fuck you, man, it’s right for the character.

At this point, Mr. Cranston suddenly dies for no reason whatsoever. He doesn’t sacrifice himself for his son, or die trying to redeem himself, or punish himself for a past sin. He just goes ‘Ah’, and then, very confusingly to the point you’re not even sure that it happening, is just dead. Now, having explained that Mr. Cranston is the only one who can solve the mystery of Godzilla, the military and the secret corporate intermittent monster hiders turn to his son, who knows nothing about Godzilla, at ask, naturally, what you know about Godzilla. Well, he knows nothing. They killed the guy who knew something, and for no reason. What he does know about is defusing bombs.

Hoo boy.

Then it goes a bit loopy.

Now the military is off looking for Insecto, called, and I am in no way, in no way, making this up, MUTO, an acronym, and I wrote this down to be extra sure (to be fair, I was writing a lot. Six pages of notes, which is a record, and means I probably missed 40% of the film) for Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organism. MUTO! Somehow the military has decided that Godzilla is good and the Muto is bad, and there’s something about restoring balance and so on. We know this because Godzilla is swimming contentedly along the battleships on the way to the next Muto (MUTO!) location.

But we also don’t know this, because all they ever do is argue about whether or not Godzilla is the good guy. This includes a very odd exchange when military guy asks corporate scientist guy what to do: the first line is correct, the others are in spirit:

‘What I want to know from you is will it work?’

‘I’ve just spent the last hour explaining to you that the monsters eat radiation, and that any attempt to blow them up with a nuclear bomb will fail.’

‘But will it work????!!!!’

‘I forget’

But before that can be resolved (it never is), there’s a spike in radiation in a remote part of Hawaii. Fortunately, out of all the places in all the world, they have a team right there. Fortunately (this time for the audience) our soldiers have forgotten that they’re looking for a giant insect creature and proceed to shoot it with their small calibre guns. Since they have found this to be utterly ineffectual, and only aids in the monster finding and to so to squash them, they keep shooting. For the visuals? I don’t know. Maybe they didn’t have gas masks to put on to look at it with.

As the humans can’t do anything, it’s really about monsters fighting it out in various locations. So you would understand why when Godzilla and Muto are about to go at it in the Honolulu harbor, the big monster battle we’ve been waiting for, just as they’re about to go at it…we cut away.

Yeah.

So, there’s various scenes of children in some vague danger being rescued, and lots of worthless adults being killed, and a slightly offensive recreation of a tsunami which kills them both. Then we discover there’s yet another muto in Las Vegas, in yet another occasionally secret government but possibly corporate lab. ‘But how is this possible? It was destroyed!’ or ‘But how is this possible? It was dead!’ is how the line might have gone. Instead, our erstwhile Ms. Sally Hawkins says, ‘How is this possible? It was dormant!’ This is an exact duplicate of the line. They teach you a lot of things in Science School. Just not what words mean.

So they open the door to discover that the monster who was in hibernation which is the same as being dead or destroyed has broken out of the lab. The lab is in a giant mountain, and, like a government but maybe also corporate security truck, he has broken out of it, all four hundred feet tall of him, without making a sound. He then proceeds to nearby Las Vegas. A ha, you might be forgiven for saying, the monster will destroy the city, the only point in watching these damn movies. And as it approaches…we cut away.

In keeping with the film’s desire not to satisfy the audience, I will now attempt to explain Blando a bit, who’s got the kind of forgettable quality of someone or other. There’s a scene at one point where they’re all in helmets and jumping out of a plane and you’re looking around: is he there? Is that him? Is that one? No, it’s no…And you realize the producers have finally done what video games have been doing all along: they’ve made an NPC into the lead.

Anyway being a bomb diffuser, there’s going to be a bomb. It’s on a missile and they want to detonate it the harbor outside San Francisco. So they do what anyone would do.

They send it by train.

MUTO!

This is the point where one of my favorite lines occurs, ‘Attention personnel. These weapons are headed to San Francisco. I have no reason to announce this out loud, as everyone here already knows this, including the audience, who has been told three times what is happening, but someone handed me a microphone, and you know how that is, you just blurt something really stupid out, just want to say something clever, but you just say something weirdly factual that everyone knows already’. I may have embellished, but the first two sentences are correct. It’s as if they wanted to remind the lead, who really doesn’t come off as very bright. Did I mention he’s an expert in diffusing bombs?

So there’s some train stuff, and we learn that there are two MUTOs, and male and a female. Funny thing is, the female gets pregnant without actually meeting the male. Honestly, this is what you’re going leave out?

So they send Blando to San Francisco to either defuse the bomb because the city is abandoned, or to set it off because it’s not. Honestly, I don’t know. There’s no one in the city except the monsters who they want to blow up with the bomb, but they can’t because they eat radiation. I’m not high, I’m relating it in real time.

The monsters battle it out for a bit, and finally, finally, we get to see a city destroyed without cutting away. Now these scenes – and aren’t we pixelled out at this point when it comes to disaster movies? – would be ordinarily pretty ordinary. In fact, I kept thinking that they were going to New York since I remember a crushed Statue of Liberty in the trailer. Or was it the Planet of the Apes trailer? X-Men? I don’t know, and though I mayest see the films and the trailers a hundred times, I still won’t. But as the city is destroyed we’re treated to various shots of Chinese lanterns blowing in the wind, and skydiving straight out of Hellblazer (the comic), and the various arty touches upgrade these scenes to a Studio City rental eggshell flat white.

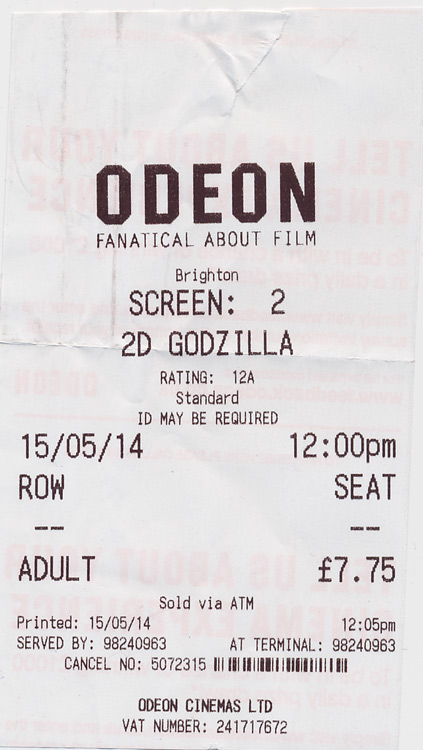

I get that we have to get these crappy tickets when the box office is shut because of the $10 a year they save, but Friday at 12p? Where is everybody?

Finally Godzilla, having seen the truck appear out of nowhere, sneaks up on MUTO 2 (he’s eight trillion tons, but it’s a stealthy eight trillion tons) and does fire breath battle ending power that he, like, totally forgot he had, and adieu poor MUTO 2. MUTO 1 was already dead, but who knows why or how.

Blando, now proceeds to press the ‘Nav-Auto’ button on the boat with the bomb to take it out of San Francisco harbor in ten minutes. Now sometimes I add a sentence of dialog for effect, and other times I just make up what I’m seeing, but let me clear: There’s actually a ‘Nav-Auto’ button. And he presses it.

It’s awesome.

And Blando, on a boat with the bomb, after we have been told that this is the one thing he can do, proceeds to not defuse the bomb in any way. No, instead he passes out and is rescued by The We Rescue Guys In Boats With Bombs Squad (that’s the one thing they do), who save him in the nick of time and there’s an explosion that we don’t see really very well.

The end.

Please understand that I have left out many, many parts that beggar description, some of which I will relate at the summing up. To be clear: do not see it. This is a much less strict version of ‘don’t see it’ than I proscribe for Calvary. Though maybe I should say that you should see it, so that you’ll trust me forever. About not seeing it, which would cause you to mistrust me. So don’t see it!

But in bothering to think about this movie, you are confronted with a film that wants so desperately to be a mystery. What I actually liked about the pretty okay Pacific Rim was that it got the set-up (giant monsters!) out in about three minutes. You know there are going to be monsters, and so here they are. It works well, but that was 2013, so even the terrible movies were going to be fairly good.

(Briefly: I remember the Betchtel test being applied to Pacific Rim, which involved a girl not only kicking ass, but even having a back story, and therefore it doesn’t matter if she talked to another woman about her feelings because she actually does something to affect the outcome of the story. In Godzilla, Ms. Olsen’s purpose is to 1) be a nurse (yep, they still give women the caretaker’s job in movies), and 2) at some point, go ‘ah!’. My favorite part of this pre-feminist dilemma was her saying to Blando as they’re evacuating San Francisco: ‘I’ll wait until you get here!’. When I say she does nothing, I mean it.

She can’t even drive a car.

Monsters, Mr. Edwards’ first, was a modest but occasionally tolerable film that may have received more attention than it deserved. As he hath moved into the realm of the unlimited, the results have becomes increasingly diffuse. There is the feeling here that when you can do anything in a movie, you proceed to do everything. There’s secrets, and conspiracies because we all love those, but then a lot of talk about how they can’t possibly find 400 foot monsters when they can read license plates of people who complain about JJ Abrams too much. They wanted to make Godzilla the good guy, but that means that the humans do nothing. They wanted so much not to make a mess, so they made a spectacular one.

Normally, this would be a kind of ordinary Transformers terrible, but it just piles on trope after explanation after nonsensical, and thus creates a kind of camp singularity. And seeing these two films so close together, I have had the benefit of being able to remember both feelings so distinctly. The first, a good original and well-written film unintentionally creating the feeling of utter contempt for a precious nihilist, and the second, bad film, radiant joy at what can only be understood as a parody of big-budget disaster pictures, even if the parody was unintentional. It’s a lesson in why we should go to more, not less films. Movies make feelings, and nobody knows how that is done. And if the filmmakers don’t know what’s going to come out, neither do you. So don’t see either of them. See everything.

The Take: Godzilla 2014

$8.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]