The Sum of Its Bits

I’ve been doing internet dating lately, and I’ve found, through repeated rolls of eyes and various ‘Oh my God. Look at the laundromat over there, how long has that been there? Isn’t it interesting how things…exist in space!’, that there is nothing – nothing except for one thing – more boring than talking about internet dating.

Nevertheless, we are here to talk about the Mr. Ryan Gosling Œuvre and the happy coincedence that both Drive and Crazy, Stupid, Love came out in the same week in the distributor unfriendly UK. Strangely the orphan of the English speaking world (every other country in the world has seen Midnight in Paris except the one where the language originated), films come out here in the most ad hoc way imaginable. I think it has something to do with the metric system. Lucky me, we won’t get Thor 2 until 2013. Unlucky me, Thor 3 will come out the same day. I won’t be able to understand a bit of it, since the original comes out in 2023, just in time for the actual Thor to revisit the earth and set all the movie schedules right again.

But you know I was just lulling you into a false sense of irony, and at any moment I’m going to talk about how films starring Ryan Gosling are somehow very much like my meeting strangers for drinks and trying to figure out if I’m uncomfortable or extremely uncomfortable. Don’t want to talk about internet dating? Fine, I’m on this diet right now…

I thought that might shut you up.

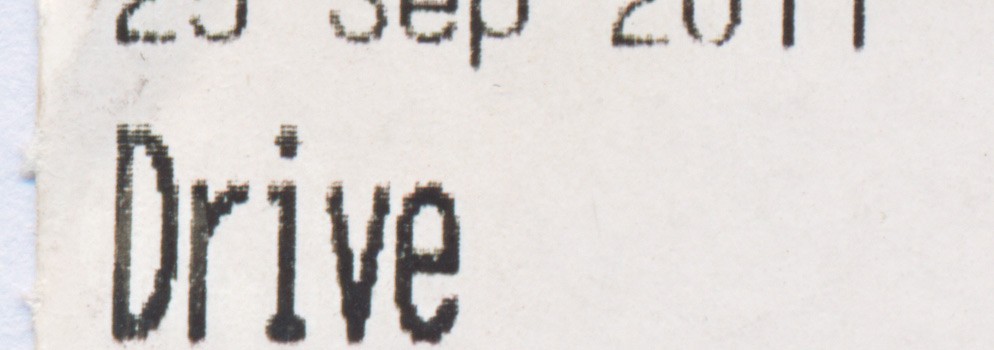

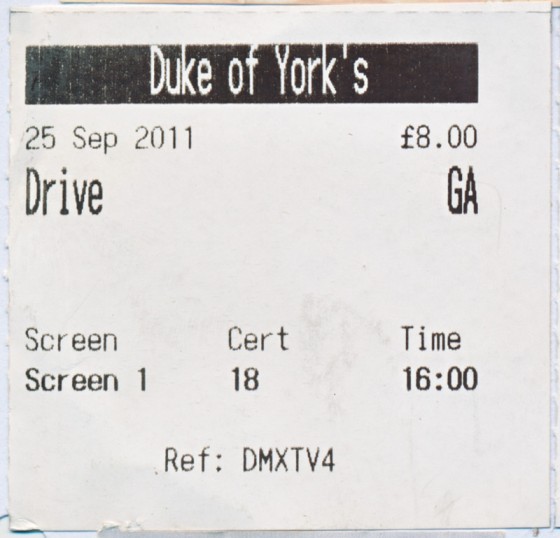

Drive, to get back to today’s theme, is the girl I’ve met online rather a lot. Nice, pretty, intelligent, perfect on paper and ticks all the right boxes (sorry I’ve been here so long I’m not sure if that’s a UK or US expression. Let me check my wordictionary). But that spark isn’t there. The actors, the script, the aesthetics, everything about the film should work. Even the narrative, and you know how much I like structure, is pretty solid, with all the characters wanting specific things (romance, money, career), making choices, and reacting to when situations change. There are even enough good gags, and memorable bits that every good film should and does have.

Saturday night, ticket bought online, arrived 15 minutes early to get seat, and still saw the damned Stella Artois ad.

And yet, we’re going to awkwardly shake hands at the end of the night and never speak again. Why? What’s the matter with you, self? You should like Drive. It’s even an example of one of your favorite kinds of film: an artsy director working inside an genre (see Mr. David Hare’s very recent and awfully good Page Eight on BBC, or Mr. Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog). This is in no way a strike against, but another reason that the film should succeed. Genre grounds the otherwise diffuse, allowing the more artistic flourishes a chance to have a purpose within a story, as opposed to just sit there and wait to be adored by critics who get the reference of V.I. Pudovkin’s Mother seen as an allegory of Caravaggio’s John the Baptist? How witty! And what pleasure they will take in explaining it to us (lordingitoveryoufreude?), at least until an actual film comes along.

Drive, sadly, is not an actual film, but a series of shots. Seeing the genre from a new perspective hasn’t made it raw or funny but antiseptic. This is best understood in the action scenes, which, like the incompetent (and much, much, much worse) Hanna have been overly and incorrectly praised. Here they are mistaking the well framed for the well shot. I can understand the mistake.

Action sequences in modern films are criticized, and rightly so, for being dull and wasteful. They are the vestigial offspring of the cop shows of the 1970s, which, needing to be exactly 52 minutes long, simply added 44 seconds of an Impala making a left on Powell, followed by another Impala making a left on Powell whenever they came up short. Oddly nowadays these scenes are the best part, as you watch them and exclaim: oh my God! Crocker Bank! Did that even exist? And look at that font!

Today, we are treated to the CGI equivalent, filler in a different, and much more expensive, form. If we have a scene where a character must ‘get over there’, or ‘kill that dude’, there’s a lot of flashy flashy and shiny shiny, but if you can’t tell what’s going on, it doesn’t count as story. Whenever I feel these dull and inevitable sequences coming on (the Transformers films are rife with inaction scenes), I keep myself entertained by imagining a team of superprogrammers, very excited about shot 26, where his kind of double anti-aliasing between a transparency layer and a rasterized hair simulation has…like…never been done before. You wouldn’t understand; it’s a Maya thing.

I take pleasure in the fact that someone liked it. We’ll call it freudefreude; joy in other people’s joy. Unless it’s a film critic, of course. I’m not the Buddha.

In all this mess, however, we are occasionally, very occasionally, treated to the Narrative Action Sequence. Narrative, it could be, and is about to be, called a combination of trajectories, characters’ desires crystallized in tangible motives. The action scene can be, and rarely is, an opportunity to become a movie within a movie, where the motives (I want me my Reese’s Peanut Cup triple pack), obstacles (there’s a bunch of zombie vampire Napoleonic soldiers in my way. Sorry; got tired of Nazis), methods (I’ve got a broken chair, a distributor cap and a half-finished TV Guide crossword puzzle) and actions (I use 2 down (‘KUFFS’) to frustrate reform in the post-revolutionary government) can all play out as a story. That is, we know what’s happening, and, second by second, root and are crushed by momentary and fleeting routs and victories.

Being a director requires no actual real world ability; it's as if becoming a rock star by playing Rock Star happens in real life.

In the case of superior films, or inferior ones with superior bits, like Children of Men, Die Hard, The Matrix and The Terminator, T2: The Rise of the Machines, and more aptly, Mr. John Frankenheimer’s Ronin and To Live and Die in L.A. (the latter which the filmmaker references, not ineffectively, the music and title sequence. In other words: look at those fonts!), each shot tells a piece of the story, which leads to another, which leads to another. Mr. Bruce Willis saves the hostages on the top Nakatomi Towers. Which means Mr. Alan Rickman will set off the bomb. Which means that Mr. Willis must improvise with a fire hose to escape the explosion. Which means he’s left in front of an intact window. Which means he must shoot it to get in. Which means when swinging, the fire hose comes loose. Which means that it starts to drag him out. Which means he has to loosen himself from the thing that just saved his life. And so on. In the best sense of the phrase.

The sequence above is about 40 seconds long, but each moment is an action. Every action has a repercussion, which leads to a new choice, and a new action. We have to remember that we’re talking about movies, and the word ‘movie’ has its root in another word. The word ‘movi’, I think.

In the case of Drive and the more ugly Hanna, they have substituted aesthetics for CGI nonsense, but the effect is the same: a sequence without narrative, and thus without tension. It doesn’t matter if you like Weird ‘Al’ Yankovic’s early and late work, walks on the downs, doggies, pear pistachio tarts with baked meringue finish or even the films Driver and To Live and Die in LA, I just don’t ‘like you’ like you.

Editor’s note: Saw Driver, at the delightful Prince Charles in London, and didn’t realize that Drive is, in fact, a shot for shot remake. Anything good (that he didn’t talk, the occasional long shot, the LA locations, the Driver’s code, etc.). There are two depressing things of note.

1) Driver was half full, and an all male audience. It was doubled with Drive which was utterly sold out, with a largely female audience. This was briefly depressing, as it interfered with my ‘meeting a girl at a movie’ fantasy, as in – if only I had picked the right movie, there would be the perfect single girl and and we would bond over Weird ‘Al’ Yankovic’s later work (very underrated) and so on. For those of you who still harbor this fantasy (hey, that’s me!), this will never happen. I am the test case. I have seen close to 10,000 films in the theater and I really am the guy at the who snuck out after Berlin Alexanderplatz to see He’s Just Not Into You. If it could happen, it would happen to me. The fact that I run in utter terror should a girl say hello has not occurred to me. Nor should it you.

2) Driver was not very good. Do not take my word for it, as Richard enjoyed it mightily. It is certainly worth seeing for the LA locations, and a fetishistically young Sophie Marceau. The latter has aged well, the former has received a botched face lift. Read it again. In any case, not much happens (see ‘Richard likes crime films where nothing happen’, not above, but implied nevertheless), but it is, however, four hundred and sixty-seven times the film Drive could hope to be.

The Take: Drive

-$0.50

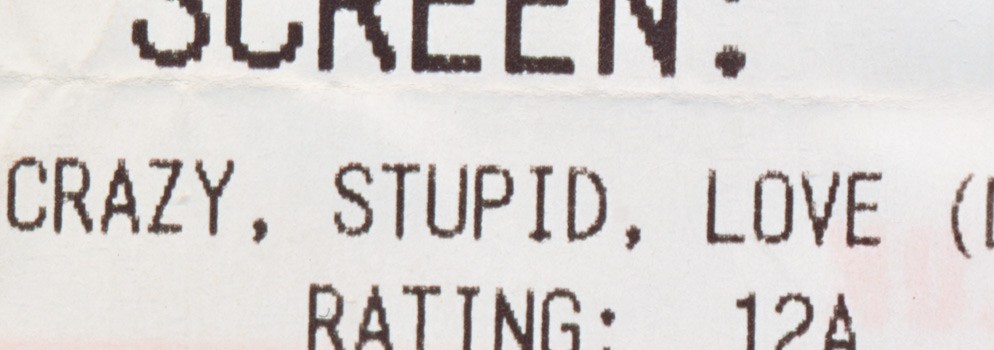

Crazy, Stupid, Love, on the other hand, is the girl I like and don’t know why, as well as being about the girl I like and don’t know why. It is the vastly superior film, because it does have that spark. There must be a rule for it, but there isn’t. In fact, the film violates my most cherished belief: that the writer is king.

This would be a topic for a much longer post, but I’m an advocate of the ‘author theory’, which stands in strict opposition to the hateful ‘auteur theory’. Directors do not make films. Putting aside the vast cooperative machinery that exists in film production anyway, the director remains around the eighth most important person. The order would be: writer, casting director, editor, composer, supervising producer, actors, director of photography, gaffer (that’s real thing: they set the lights, and I’m being serious here), then, arguably, the director. Nrs. four and five can switch occasionally, but that’s all the flexibility you’re going to get from me.

Directors occasionally make decisions – occasionally – but for the most part just watch as the clockwork spins, and then take credit as a function of the law of large numbers. No one has any idea why a film should be good or not (except for me apparently), and we assign credit by function of not knowing where else to put it. That, and the fact that being a director requires no actual real world ability; it’s as if becoming a rock star by playing Rock Star happens in real life. Fortunately for the business and the public, the auteur theory is rarely put to any empirical test, in that directors rarely produce consistently good (or even consistent) work (the exception being writer/directors: see the first word. Writing is hard. Especially if you’re doing it for free). In the way that we drive like total assholes and rarely check to see if we got there any faster, we credit directors with being good if they made one ‘good’ film, but don’t check if they’ve made shitty ones. Which they often have. Mr. Ridley Scott ‘made’ Blade Runner but also Legend and A Good Year. Mr. Clint Eastwood ‘made’ Unforgiven but also True Crime and Space Cowboys. Mr. Terry Gilliam ‘made’ Twelve Monkeys but also The Brothers Grimm.

David Peoples wrote films one, four and seven.

That’s the author theory.

But there, on the end credits Crazy, Stupid, Love was a sincere apology for yet another forgettable title on a good movie. No, there wasn’t, but there was a credit: written by Mr. Dan Fogelman. Cars Dan Fogelman? Fred Claus Dan Fogelman? CARS 2 Dan Fogelman???. There’s no way this man came up with this story, these characters, and the line: ‘The war of the sexes is over. We won when women started doing pole dancing for exercise.’ He couldn’t have conceived the terrific character moments as when Mr. Steve Carrell secretly gardens his estranged family’s home. In any other film, this would be a pretext to be discovered and create narratively convenient embarrassment. But here it becomes instead a set-up for another moment when Ms. Julianne Moore calls him and lies about the water heater pilot going out. They’re both lying to each other, and they don’t get found out. My notes: ‘don’t spoil this, don’t spoil this’. Any other movie would have. This one didn’t.

And so I must begrudgingly accept the auteur theory, especially since the directors in question (and don’t get me started on Movies Directed By Two People), are Mr. John Requa, who wrote Bad Santa and Mr. Glenn Ficarra who directed the bafflingly underappreciated I Love You Philip Morris. They were the ones that captured the feeling of meeting someone that you wind up talking with all night. Mr. Ryan Gosling, perfectly fine in Drive is better in CSL as he manages to nail both the charming and callous pick-up master, and the vulnerable man within. It’s not an astonishing performance, but a transparent one, which is so much more to its, his, and their credit.

I’ll admit that my newfound, and temporary, embrace of the idea of of director as God is merely a stopgap in the face of scary, scary luck, unable to face the fact the films simply pop into being without any explanation. And in the UK, without any schedule. And so, as I walk away from Guardian Soulmates (I felt you were getting too not uncomfortable), utterly convinced that ‘I will always be alone’, this is my auteur theory, a way to sell my puny human brain on the idea that it knows is, will or has happening, happen, or happened. Films are as random as people, a product of egos and coincidence, half contingent on what they are and what I thought they were. So, don’t listen to critics, don’t listen to your gut, and whatever you do, don’t listen to your brain. Just get in line, and ask for the ticket to whatever’s next.

And yes, that counts as a rule.

The Take: Crazy Stupid Love

$9.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]