The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

You did. But I would have.

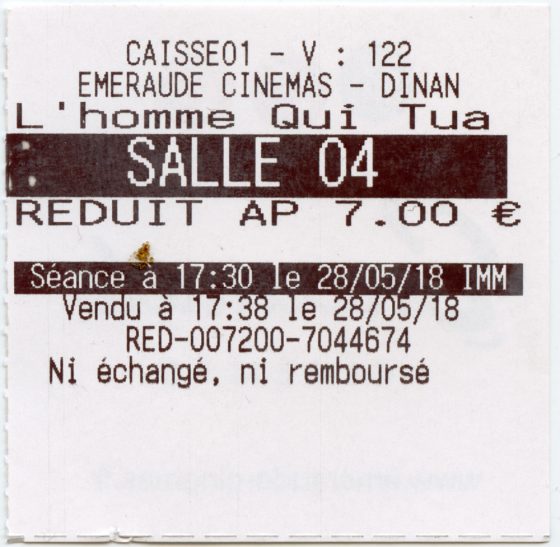

Well, there was a worse film than Avengers: Infinity War, and I saw it. There were many bad signs before seeing The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. The first was that the ticket seller told me ‘Vous seriez tout seul’ (‘You’re going to be all alone’). It was the first time in France that I saw a movie by myself, and that is never a good sign in a land of chronic movie goers. It’s like they left before it even started.

The second was the number of production companies before the credits, like everyone wanted to say that they were involved in a Gilliam film, just not so much that it would pinch when the check came.

For a film twenty-five years in the making, it feels rote, like the first draft of a neophyte who thinks that his dreams will make a good film transcribed – seemingly verbatim – to the screen. There are an infinite number of ways to tell this story and the film manages to combine all of them to make none. It’s a film that shouldn’t resemble Ready Player One but does – it moves from one scene where nothing happens to another where the story doesn’t exist to another where characters are not developed.

This may be because it is based on a novel seemingly no one has ever read. Did they at least see the musical? The evidence for this assertion is that the number of

windmills

in the film, and I am not joking, caps out at seven. The film is not joking either. On any level. Windmills and windmills and windmills. It’s like making a movie about Han Solo and mentioning the Kessel Run four thousand, six hundred and EIGHTY-ONE TIMES.

Nobility

The film also quotes the opening of the book many times, maybe so youze mighta feel like someone managed to get halfway through the first paragraph before giving up and saying they could do better.

Unfortunately, actual nobility is in short supply in a world where women are either whores who need saving, or whores that are sex-crazed. That’s not true. There’s a PA with a few lines who decides to become a whore.

What? We gave the female character agency. What are you complaining about?

Innocence Trashed

This is not a theme of the novel, but a perfectly acceptable one. Mr. Adam Driver is a now cynical filmmaker, remembering and rehashing his old glories as commercial director. The contemporary world of advertising is not convincingly painted, broad stroke shallow characters would have seemed dishonest and lazy in the 1980s.

But the fundamental problem is the pre-fall world (shown in, yeah, I know, black and white) lacks an ending. The climax (see below) told me that we’re supposed to feel bad about using people or something. But Mr. Driver never does anything unkind to achieve his career goals other than be bland and enthusiastic.

If the story is idealism to cynicism and back again, there has to be a moment, a choice, where he did something to earn his punishment.

Ah, making sit through even the slightest sequence. It’s clear to me now.

I agree. Reality IS stupid

During Mr. Driver’s first film, Mr. Jonathan Pryce is a shoemaker found in the village as the one perfect to play Don Quixote in his indie film. Later, in an agonizingly slow reveal, we find him twenty years later, actually believing that he really is Don Quixote.

Where do they get these ideas?

This may be Mr. Driver’s great sin, that he, uh, cast somebody in his movie. This remains perpetually unclear because of Mr. Gilliam’s greatest motif: the perils of reality versus the joys of fantasy.

Unfortunately, whatever tightroping skill he may or may not have possessed in the past is gone, and in its place our doubt that he ever had it. Unsure what left is which up, the film suffers from either not knowing itself, or worse still, not letting us know, what passes for reality.

Which is fine (it isn’t) as long you don’t expect us to care. The climax (see above for reference ‘see below’) is the humiliation of Mr. Pryce at the hands of Mr. Driver in front of Russian Oligarchs (see ‘broad shallow characters’, now above). I guess they want spend a lot of money building a carnival environment to make impoverished Spanish shoemakers face their delusions.

That has got to be a very big bucket list.

Mr. Pryce, now aware of reality so that there can be a beat at the end, is sad. He says ‘You could have stopped it. You didn’t.’, implying a universe coherent enough for the existence of pronouns. Obviously this is his ‘moment’ but it doesn’t have any sense; it’s a second act break without anything before it.

And therein lies the/another problem. Sometimes the characters are aware of what’s real, sometimes not, but we never are. Surrealism needs discipline, perhaps more than any genre. The delicate balance of feeling needs a solid place to put the fulcrum.

And, if engaged in such shittery, don’t say: ‘Please don’t let this be real’. You don’t want to give me something to repeat, both out loud and very. I was in the cinema by myself after all.

They’re called QUESTS, dickweed

Pick a quest and stick with it. That’s possibly the definition of a quest, or even a definition of a story, what with Don Quixote being one of the first novels ever written. Having unmotivated characters, or even unclear ground, makes any kind of quest de facto impossible.

You were left instead with the feeling that the film was the quest. Mr. Terry Gilliam was trying to show how he had weathered and endured those executives and Acts of God that had famously torpedoed the original.

Well guess what, sucko? I was trying to show you that you could throw any amount of uninspired satire, featureless characters and DOA tension or interest at me, and I would fucking well stick through its two hour plus running time.

A man in a cinema, trying to see, and survive, anything. That’s a quest.

Please don’t make that movie.

Okay, g’head. But I’m playing myself.

The Take

-$26.99

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]