Bullets or Ballots, In a Lonely Place & The Maltese Falcon

Unholy Cow!

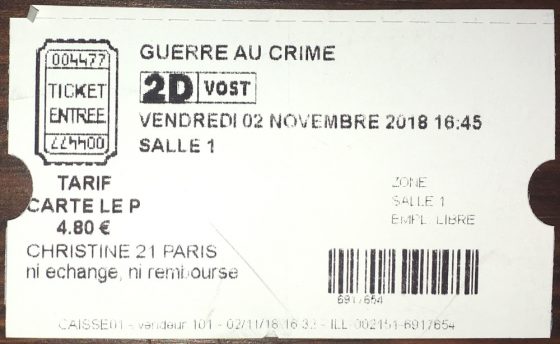

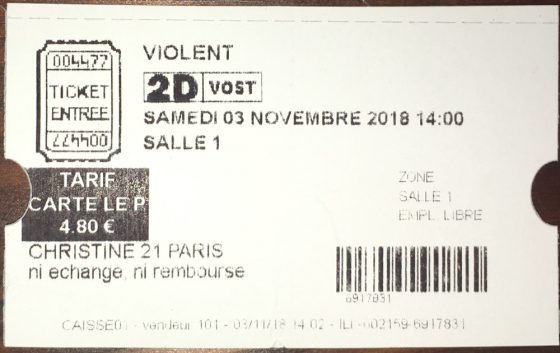

Wouldna seen Bullets and Ballots, having never heard of it, but it was being projected at the Christine 21 in glorious 35mm, so off I went. The next day saw the much better known, and thereby significantly more terrible In a Lonely Place the next day (in digital). The former has a lot to teach the latter, in the ways that films teach things about each other.

Bullets and Ballots has a lot going for it. It starts in a markedly original way, with the two gangsters buying tickets for a newsreel about themselves. It’s the best exposition I’ve seen in a while, and I can’t believe no one has stolen the idea. Probably because everyone was seeing In a Lonely Place.

It’s good to know the French have been a-retitling, at least since the 1930s. But in this case War on Crime is better.

After that, Mr. Edward G. Robinson has a lot of snappy lines, maybe goes to work for mob boss Mr. Barton MacLane, maybe it’s undercover, maybe it’s not, and – very sagely – the film reveals the answer about halfway through. It knows right when to tell us. The final confrontation between Mr. Humphrey Bogart and Mr. Robinson is not as satisfactory as I would have liked, but I cried twice and laughed a lot.

The one aspect I’m going to single out is Ms. Joan Blondell’s character, one with actual agency. This female role was in shocking contrast to In a Lonely Place, made some twenty years later, who must decide whether or not to stick with a drunkard abusive husband. The spoiler in that instance – it’s her fault.

Anyway….

In the case of Bullets and Ballots, Ms. Blondell runs a numbers game in New York, so she’s an actual player in the story, and Mr. Bogart, because he’s a thinking villain and not just following the story beats, uses this to his advantage. When her friend Mr. Robinson steals her business to get in good with the mob, the following scene takes place between Mr. Bogart and Ms. Blondell.

In other words, stick to business, chump. It’s as nice to know that women could actually do stuff in 1930s films as it is depressing to know that it remains just as anomalous today.

Bullets or Ballots – The Take

$11.00

…and twenty years later, when In a Lonely Place was made. I mostly don’t get how this film – an extremely underdeveloped and style-less version of Suspicion – could be considered a classic, dramatically inert as it is. Ms. Gloria Grahame is perpetually not sure if Mr. Bogart killed a woman, and then, very gradually and having nothing to do with the actions or choices of the characters, we find out he didn’t.

You kind of get why the film was made. Mr. Bogart plays a nice guy with a very bad temper. It’s a gritty role, and he does fine navigating the poles. There’s some implication of sex and sleeping over, though considerably less than the pre-Hays code 1931 adaptation of The Maltese Falcon. It’s a film trying to break out of its time. From the vantage of now, they’re trying to make a Mr. Nicolas Ray revival happen. I don’t actually care they I should: this might actually demonstrate that directors have nothing to do with films.

Whatever and whoever its own origin, the film is very much of two minds. On one hand, Mr. Bogart is a short-tempered drunk of whom Ms. Graham should be wary. On the other, the discovery of his innocence at the end implies that it is this which is to blame for the downfall of their relationship, and not, say, the fact he almost beat her to death. It’ll never happen again, honey. It’s not me, it’s just the stress… that you’re causing me! Exit Mr. Bogart, a victim of circumstance.

…and here called Le Violent, which speaks to a theme to which the film fails to rise. But the chocolate – from nearby Un Dimanche à Paris – was fantastic. Must recommend the Christine 21.

Safely on the perch of history’s diaspora, you can be justly critical. Eww. You get the distinct impression the filmmakers had an interest in this subject, either as a character or a social problem. Just not so much that they wouldn’t be called on the carpet for beating their own wives.

You know. For the good reasons.

This lack of commitment to the subject means we attach ourselves to the stupid murder, which in turn leads to an detachment to the events happening in front of us. His innocence or guilt becomes paramount instead of his behavior, which is what we get to watch, and what is supposedly be dramatized.

Whereas in Suspicion, the tricks and clues are ambiguous and yet conventional enough to keep the audience believing they might do the same, and further occur in front of the lead (Ms. Joan Fontaine) herself. Waiting as we do for the final resolution to happen off screen, In a Lonely Place must explain to the audience how much in love Ms. Gramme is, how good Mr. Bogart is deep down. And if you need to explain to the audience, maybe you should think about a visual medium.

In a Lonely Place – The Take

$0.00

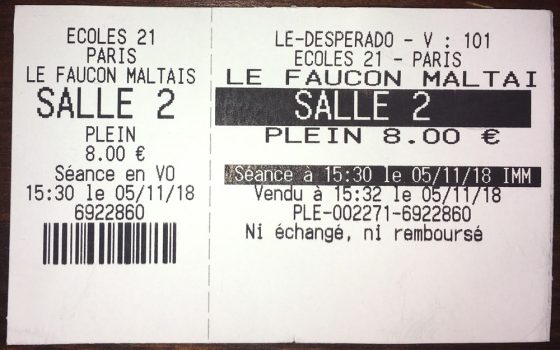

The fourth Bogart film in just as many days (left out the very bland The Enforcer, upon which it seems many a Law & Order: SVU was based) was the unassailable The Maltese Falcon. But I must assail, as is my wont. I was happy to get to see it in 35mm, though the print is held together with very scratchy cut-tape indeed.

Without the benefit of the doubt foisted upon an impressionable twelve-year-old seeing it for the first time, The Maltese Falcon just doesn’t hold up. There is a staggering amount of offscreen action, important to the story, and really needed someone like Chandler, or Hammett for that matter, to spice up the dialog.

The film does have its moments and its characters. The floridly written Mr. Sydney Greenstreet is a prize. But I’m not crazy about mysteries, and this film elegantly demonstrates why – the murder could have been anyone at anytime with any object. In the Conservatory though. It’d have to be in the Conservatory.

There is scene-where-ism up the abraham (it was the 1940s, and that sounds way dirtier than wazoo). One especially odd scene is where Mr. Bogart plays it tough and walks away, with his smile indicating that he was just gaming them. Good idea, it’s just that there’s nothing more he gets out of the act, and it comes off as a ‘wouldna it be swell if’ moments, something they had to leave in.

Likewise, there is no reason for Mr. Sydney Greenstreet to tell Mr. Bogart the actual true story of the falcon while he’s drugging him. I get that this is a ‘clever’ scene, and you need the exposition. Doesn’t give it any more sense.

After much happens outside of the viewpoint of Mr. Bogart to be explained later in drawing rooms (Conservatories if you must), and Mr. Elisha Cook Jr. is set-up to be the fall-guy because they absolutely need him until they decide on a dime that they don’t need him after all, the statuette is revealed to have been a ruse all along, Symbolic Of Our Venal Desires (and a famed but always clunky faux philosophical curtain line).

Oh right. Can I say something the twelve-year-old wanted, and he can now dare: it’s a shitty prop? If it was encrusted with jewels, you would see the outline of the jewels. Then again, it wouldn’t be 1930s streamlined, so never mind.

Emblematic of the scene-where-ism is the ‘clever twist’ at the end, where Mr. Bogart gives up Ms. Mary Astor for the murder of his partner, whom he was cuckolding and whom he didn’t like. And I’ll confess: ‘You killed Miles and you’re going over for it’ is a nicely turned phrase.

Problem is, they know each other for a day, and they fool around a bit, and at every turn she lies and tries to kill him and sell him out. Ms. Astor is a creep by any standard, the 1940s version of a 1950s man who is constantly drunk and beating people up, for example.

Its faithfulness to the book (as was the case with Mr. Raymond Chander’s famous didn’t-know-who-did-it-was-hoping-you-could-tell-me anecedote from the adaptation of The Big Sleep) was not an asset – these are problems of the text that can be overlooked when explained in VO, but less connectable when seen on screen. Though I’m grateful Ms. Astor is not a doormat, giving her up is no great loss, and despite being another ‘classic scene’, generates now, as it did then, appreciation, but no feeling.

The Take – The Maltese Falcon

[logo]

[logo]

Bum steer is translated as mener en bateau.