Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

The Deathless Abattoir

I cried at the end of Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, but as is obligatory with films such as this, there’s a twist. See, during the tedium that unspooled before me, I noticed a girl, about eight, seated next to me. As film amped up its talkiness and tedium, the girl, like me, became more and more fidgety. At some point, she reached down and retrieved what I thought was a stuffed animal, certainly more fun and more soulful and better filmed (having never been filmed) than the mess we collectively witnessed.

When the lights went up, I saw it was stuffed animal: a little German Shepard puppy, and of course I choked up, having had a German Shepard named Snoopy at a boy. You would think you couldn’t put a scene like that in a film, too on the nose. But it works because it’s a grumpy old man who hates kids interrupting his coffee and desserts, suddenly moved by the innocence and boredom of a little girl.

But it also fits within the context of the film, whose sole interesting element is Mr. Eddie Redmayne’s Newt, the one who knows how to talk to animals. The only time the movie connected (and the audience agreed) were his interactions with animals. Making a giant scary Dragon-Dog chase a toy is solid bit, though only because Mr. Redmayne sells his character’s basic and awkward decency so well.

Unfortunately…

…there’s a whole movie set around him, one to which he does not belong. He is, we’re told by Mr. Jude Law’s awkwardly inserted and retconned Dumbledore, the only one who can Find The Boy. Except that his Doolittle talents are not suited, even in this consistently convenient universe, to finding people. And so, other than an occasional random Platypus that makes the experience tolerable, he just does stuff anyone would. That’s it.

Not even fitting into the plot, Mr. Redmayne certainly belongs elsewhere than Ms. J.K. Rowling’s forced parable on Trumpian Fascism. A nice speech about ‘not saying what we really want’ and an utterly brilliant concept of protecting the magicking world from the real horrors of World War II are squandered by an increasingly obvious and campy evil. Seemingly unaware of the famed ‘Are we the baddies?’ (meme or sketch):

The stridency, and worse yet, the attempts to hide it, are not compelling to me as an eight-year-old girl with an adorable stuffed dog. It’s what a fascist would do.

Now politicizing films can have success or failure, but the crime of the film from a boredom perspective is naturally enough, its secrets. The Girl and I sat glassy-eyed, unmoved as the character reveal their Great Secrets. Our shared disinterest was not just because the secrets aren’t that compelling, or because other characters know about them (meaning they’re not secret), or because many of them carry no earthly reason to have them concealed, or because EVERY CHARACTER SEEMS TO HAVE ONE. It’s because – and the girl with the German Shepard puppy will agree with me on this – of how fucking long it takes to explain them.

Ultimately, what all these secrets are really are about are hiding writing flaws. Mr. Johnny Depp explains how manipulating Mr. Ezra Miller is all part of ‘his plan’, without actually letting the audience know what that plan is. Is there anything more dull than a plan, even an evil one, that goes right? Without the very basic mechanics of things going wrong, even knowing what could, we feel nothing.

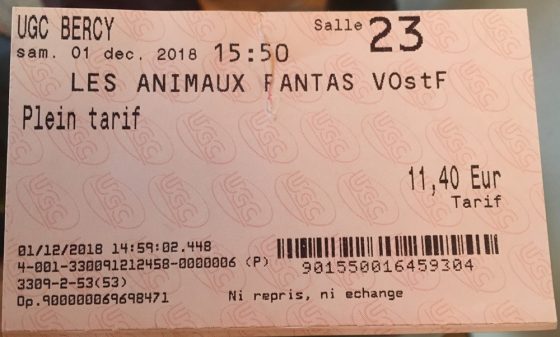

I’d like to hate the Gilets Jaunes, angrily protesting their…anger, I guess, and that their violent street destroying causing me to shift from Gaumont to UGC and actually pay for this film. But like great -and earned – coincidences, their unnamed rage led me to the front row of Salle 23 and the girl with the stuffed German Shepard. Write that movie about the heart of crowds, Ms. Rowland.

I’m writing too much about a non-entity of a film, and not enough about a truly terrible one (Bad Times at the El Royale). No doubt I’ll get to that, and write too much about it. My procrastination is all the more pointless because both films have so much in common. But I was reading Sig. Franco Moretti’s excellent and excellently-titled essay, “The Slaughterhouse of Literature.” and it seems to pertain.

Sig. Moretti wonders why, out of all the many many mystery authors of the late 19th C, only Sir Arthur Conan Doyle emerges as one we continue to read. Not unlike me (always a compliment), he decided to comb Strand magazine from 1891 to 1899. He saw the bad films too. Well, got his doctoral candidate to.

That’s unlike me.

The distinct element they found was clues. Sir Doyle has them; his contemporaries do not. The concept of a clue was relatively new, and even Sir Doyle was struggling with it. What matters, according to Sig. Moretti, is not just the presence of clues, but that they be:

•Necessary

•Visible

•Decodable

That is, that the clue matters to the plot, can be seen by the audience and eventually transformed by a new way of seeing how it was left behind as a tag of information.

What you feel in Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald is that Ms. Rowling – in the 21st C. no less – has not learned these seemingly basic lessons. The structure of the film is, with all its secrets, a mystery. But it is a mystery by, say, Mr. Fergus Hume (damn, there’s my old-timey name) or Ms. Catherine L. Pirkis, where there is no sense that in order for the audience to have fun, we have to know just enough.

There is, for egregious example, a clue in the vaults of the Ministry of Magic in Paris that will unlock Mr. Miller’s ancestry. In another film/book, one clue would lead to another (necessary – visible – decodable), until we arrive, climatically, at the vault. Instead, Mr. Redmayne, nearly 5/6’s of the way through, suddenly remembers. Sigh.

Why are Sir Doyle’s stories read over and over, while other are left on the abattoir floor of canon? Because they provide a clue – something that don’t know, but could have. The state of knowledge just in between, not the state of knowledge forced upon us. The storyteller is the parent saying ‘Because I say so’, with an identical effect. And girls with stuffed German Shepard puppies are just too smart for this.

The best of Ms. Rowling’s work before, even the first of this series, understood this. This film does not. The film will not survive the slaughterhouse. Ironically, the animal characters inside it will.

The Take

-$12.00

Thoughts on Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

[logo]

[logo]

Ha ha ha ha, great review. It’s great when you see such pure exploitative Hollywood shlock that what you take away from it as meaningful was the art it inspired in your own heart and mind, to notice and appreciate a little soul companion. Because reality will always be 100 times more beautiful and magical than any movie.

Yes, I do see a lot of exploitative schlock, it’s true. But then good things happen too. But it’s inspired me to put it into a movie. If only one could have both: good life and good films…

Good review !

Thanks! Sometimes the stars align just right…