Green Lantern

I am dubious (green)

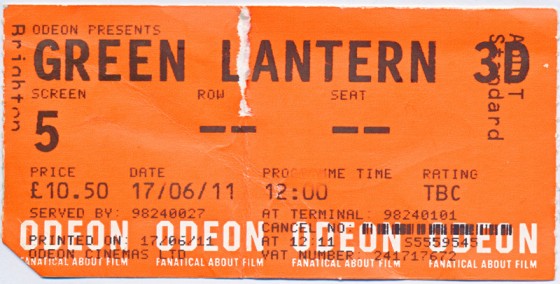

Walking out of Green Lantern 3D and looking down at 4 pages of notes and two captioned doodles, I felt a little ashamed. I knew I was going to write something, but what about my poor little Green Lantern, looking up at me with its big, well, not quite puppy dog eyes, but its big mutant yellow energy octopusesque creature eyes. Modest, from neglected DC comics, casting Ryan Reynolds despite Wolverine: The Beginning After The Real beginning We’re Saving for 2017, it only wants to be liked. To make matters worse, it is an embarrassingly easy target, the film theory equivalent of cleverly mocking politicians for being corrupt, bankers for being greedy or movies for being made in the first place. Criticizing Green Lantern is like beating a dead horse on top of a man when he’s down.

Let’s not call it criticism then; let’s call it negative growth counter-positive reinforcement….synergy. I’m not angry at our yellow energy octo-guy anyway. It’s the parents that really piss me off. Like the children of today (and totally unlike my generation, who were never spoiled in any way) I think we can safely say that Green Lantern was not so much made, as it arose out of the committee focus group groupthink equivalent of ‘Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. I mean it, Kaitlin, don’t. Don’t do that, Kaitlin. Stop right now. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. Kaitlin, don’t. No, really. Stop. No, Stop! I MEAN IT. I’M GOING TO SHIT ACID AND REIGN DOWN THE WRATH OF HELL IF YOU DON’T STOP RIGHT NOW!‘

‘Kaitlin, don’t.’

And so what do we say by way of instruction to our hypothetical parents? Well, let’s start out by correctly naming the genre. Green Lantern has been misidentified by critics and the filmmakers alike as a superhero movie, or a comic book movie, when in fact, it is fantasy, having much more in common with the Harry Potter films, The Raven, etc. Actually, I think that might be all, so scratch the ‘etc’. Green Lantern (the character; sadly not the film) has powers that are not specific (as in spider, super or aqua), but instead come from – ahem – ‘the green power of will’ (poor Green Lantern; with a premise like that, its parents gave it about as much chance as a child named ‘Porsche’. Or ‘Rumer’).

As all references to Germany's National Socialist Party are somehow both offensive, and have also lost their ability to offend, let's agree that I'm not so much a structure Nazi as a structure serial child molester who doing something gross with his eyelids.

The point being that he thinks of something, and it materializes. This causes all kinds of narrative problems as without a kryptonite to balance things out, anything is possible, and so everything is boring. The narrative of the film is like a flow chart without any options, like watching kids play guns:

‘You’re dead!’

‘No, you are!’

‘No, I’m not; you are.’

‘Okay! You win! Let’s play Waiting for Godot!’

‘We already are.’

‘No, we’re not.’

‘Yes, we are.’

‘Okay! You “win.”‘

As all references to Germany’s National Socialist Party are somehow both offensive, and have also lost their ability to offend, let’s agree that I’m not so much a structure Nazi as a structure serial child molester who doing something gross with his eyelids. Structure is what separates movies that you watch once and forget what happened from those you see many times, each time wanting to forget what’s going to happen. In this case I’m not talking about story, but one of its crucial components: instrumentality. Instrumentality is the tangibility of the goals that we can see on screen, necessarily quite simple and visual: survive, kiss the boy, kill the bad guy, get to LA, kill your deaf son in the basement bowling alley of your oil-financed mansion, and so on.

These goals are by necessity measurable: not just the rules, but the way in which the rules are visible, so we know where we are in the story. In a road trip movie, it’s where you are on the map. In a zombie movie, it’s whether or not it was a head shot. In a list, it’s making sure that there are three things, for the sake of symmetry. In a romantic comedy, it’s the wedding. With magic, there are no rules, and no orientation. J.K. Rowling solves this problem with a setup and resolution; in Goblet of Fire, the introduction of the horcrux at the beginning allows Voldemort to catch Harry via winning the contest for the goblet of fire, just as Hermione’s disappearance and reappearance throughout Prisoner of Askaban via the time-turner cleverly allows them to see her hair from the back.

Green Lantern lamely attempts setup/resolution by having Green Lantern’s training sequence include a lesson about gravity with no explanation, meaning to surprise us at the end. Sorry, inform us that we were supposed to be try to look surprised at the end. I’d feel bad about giving this away, but having read Einstein’s 1916 paper ‘Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitaetstheorie‘, you already knew that the gravitational force of the sun would be strong enough to bend the yellow power of fear.

But, like pretty much every proponent of nuclear, vegetable oil, solar and wind power, I’m willing to overlook a flagrant disregard of the second law of thermodynamics. I may be a structure human smuggler with a skin condition, but that doesn’t mean I’m inflexible.

Green Lantern could have solved the magic problem the same way The Raven (1963) did (you don’t need to see it: I’m sure that the interesting bit is on YouTube; the rest: not so great). Two magicians (Lorre and Karloff, natch) sit in chairs opposite one another and start to throw magic spells. We don’t know the rules, but it doesn’t matter since the film manages to be witty about the whole thing: when one materializes a snake around the other’s neck, he transforms it into a harmless scarf and so on. The point/counterpoint solves the problem of the characters of being able to do whatever they want, like when some hippy proposes that we can easily power the earth forever with one year’s worth of U-235.

Sorry, I’ll drop it.

We get a glimpse of potential when Green Lantern rescues a crashing helicopter by creating a giant Hot Wheels track, but as there’s nothing else like it in the rest of the film, it stands out like a orphan of a very early draft. Why didn’t he go on to materialize a giant bag of marshmallows to catch a falling Blake Lively, or a giant cricket bat to pound poor Peter Sarsgaard, or conjure 7000 foot high corn plants, which is the only way you’re going to make ethanol available to more than a half dozen people?

Okay, that’s it. I promise.

We could possibly take refuge in the last part of the actual title: D. No, that’s not right, 3D (speaking of picking on the weak, it would seem that 3D is on the way out, what with all the ads proclaiming: ‘2D in selected theaters’. I could not be happier about this as I detest how shitty 3D technology is – inversely proportional how great James Cameron tells us to think it is – but the ads are a little creepy. Like Coke Classic (you’re too young, look it up), they introduce something we didn’t want, and then offer what we already had like a regifted office secret santa scented soap that you hastily stuffed in a Whole Foods paper bag. What’s the matter with you? You could have wrapped it!).

Green Lantern is spectacle after all, and that’s fine with me. I could watch essentially plotless, but extremely beautiful and trippy films like Tron: Legacy or Speed Racer all the way through with the sound off. Scratch that: I prefer them with the sound turned off. In fact, they say that the first half of Avatar syncs up to Before These Crowded Streets. There’s a slight possibility that I made that up to make you watch Avatar and listen to The Dave Matthews Band. I must not like you very much.

Stripped of any narrative sense, light on wit and spectacle, cannot help but reveal what Green Lantern so desperately wants to be in the first place: a kind of Randian comic book primer. Without rules, plot or tension, we are forcefed such gems as ‘Your will turns thought into reality’, ‘The ring’s limits are only what you can imagine’, ‘Fear of fear is the only way’, ‘Fear is the enemy of will’, ‘They are powered by the central battery – green is the color of will’, and my favorite: ‘We must build a yellow ring!’

Nietzsche wept.

We cannot help but feel like we’ve accidentally wandered into Bob Socrates’ Big Big Book of Akrasia. But Nietzsche’s credentials aside (and Rand’s and Socrates’ as far away as a green willpowered missile could fly them), why does fear keep getting such a bad rap? There is something to fear besides fear itself, and that’s a big octoguy headed for you. And I sense these lantern types doth spake of fear and will too much. You can almost picture the filmmakers and their ilk standing on their footstools saying ‘Eek, an emotion that saps my manly energy!’. In any case, if you really weren’t afraid, technically speaking, you wouldn’t do anything. You’d just sit there and wait for the end with Buddhist calm. A shorter, but infinitely more interesting movie.

And if I had been told that it was a political tract ahead of time, I might have enjoyed it on its own level. I loved XXX:State of the Union. But this type of setup is just boring filmmaking as Green Lantern’s struggles are all internal (see instrumentality above). In what stands out as a producer’s note from a very late draft, Green Lantern is asked why he feels fear. He replies, ‘Because I’m afraid!’.

Four pages.

The film’s leanings (and narrative shortcomings) are revealed most clearly when a bunch of Lanterns confront Parallax (he feeds on fear!) the octo-like critter to whom I referred earlier. Floating through space, they get their rings together and…throw a net over him (again, not big on the imagination front). Like the guy behind me who tells the hero to just call the fucking police already, I’m fairly sure I said: ‘You can materialize anything: how about a net that’s, you know, bigger than the thing you’re trying to catch. Alternatively, hammers full of rocks carried by a bunch of space sharks with hammers full of rocks for teeth’.

But this is exactly the point; the film wouldn’t do this – not because it ends the film early, but because it defuses the message: I looked behind me, and it wasn’t the guy asking the characters to behave rationally for once, but Ayn Rand, saying over my shoulder: ‘You zee? Dhey lacked da vill!’. And without the narrative it becomes all message, the action/magic/comic book equivalent of a spectacularly self-congratulatory and unfunny political satire directed by Tim Robbins.

Hey. There he is.

The Take

$0.50

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]