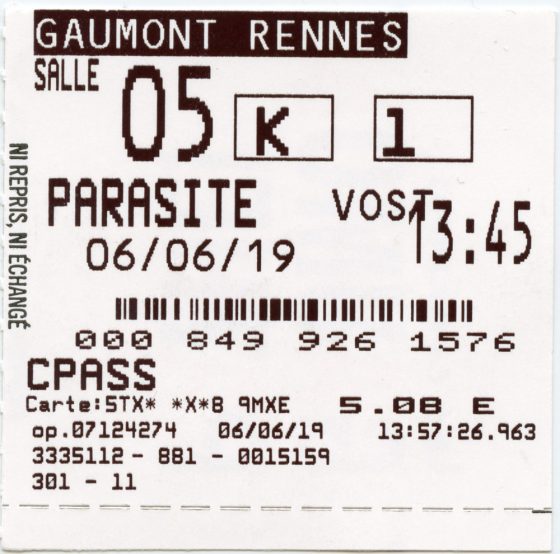

Parasite

Class Snuggle

Well it’s been a while. I have many excuses for not writing, but I only need one: I’m too lazy to think of excuses.

Dorothée mistakenly advised me to try a different type of film (even though I’ll See Anything (‘sniff’)), and so off I was to Parasite, Joon-Ho Bong-ssi’s latest. Initially I wrote ‘Having inexplicably won Palme D’or’, but this is as explicable as it gets. The Palme, the booby of the festival prizes, was inevitable for a film that has so much to say about what the rich think about what it’s like to be poor. The prize was the indicator of what other rich people think about that.

A retired boxer’s hardware store of hammer-fisted class metaphors, the film’s unsubtle Marxist title should have warned me off. But who is the Parasite? There are two meanings? At ONCE?

The story of a poor family scamming its way into a rich one by becoming tutors, drivers and nannies has some frisson, I’ll admit. But with Joon-Ho Bong-ssi’s approach, it comes with colossal sacrifice to basic story logic. The plan to fire the beloved family housekeeper depends on the wife not telling the husband. So… she doesn’t. The plan to fire the driver is dependent on the husband finding underwear and presuming that the driver is having sex in his car, instead any other of a thousand more plausible explanations. And so on.

In a related vein, when the middle of the film accidentally contains some actual action, the characters trapped in the house simply escape. I thought of Shakespeare’s comical lack of stage direction amid the ornate dialog (his, not Joon-Ho Bong-ssi’s). Exeunt, Shakespeare would say. It is applied here as an opportunity not to think things through.

They Leave.

Despite universal raves (‘Parasite is a malign delight from start to finish, with a Machiavellian sense of mischief and a cinematic brio that shows Bong revelling in his Hitchcockian control of somewhat Buñuelian material’ – why it’s three, three, three college dorm name-drops in one!

Bong is his surname, by the way, and it’s quite rude to use the honorific ‘ssi’ with a proper name. I’m using both, as is proper if, for example, you don’t know their profession, or if the subject is an entertainer, which does not, it seems, merit a metier-based honorific. A full half of the time writing this piece was spent on Korean Honorifics, which are spectacularly complex.

I don’t want to be rude.

Well, I don’t want to be accused of being rude.

Besides, it’s not Hitchcockian, which is the belated point (when it comes to verbosity, I’m more Jamesian than I am Spillaineian, as witnessed by this five, count ’em, five paragraph parenthetical. Which ends……. now!)), this is why contrivance, or its lack, matters. Hitchcock transformed the ordinary into points of tension. Bottles of wine running out at a party, forgetting a cigarette case, and, rather famously, a shower. Everything in Parasite is forced and unnatural, requiring both an explanation for its origin (

) and then another for its payoff. Without believability (theygetawayunt), there is no opportunity for what is needed most – a chance to empathize with characters in jeopardy in an explicable and relatable way.

Empathy is lacking all over the place. The Deus Ex Surprisus conceit causes characters in mainstream films to behave inconsistently (which I guess I’d go back to, if it wasn’t for non-entities like the latest John Wick installment and the final Avengers one). Here, all must serve The Allegory.

The poor family, with no experience whatsoever, are suddenly masters of the con, but then, suddenly, also of the jobs that they then con their way into. Under more competent genre hands, this would have been a story on its own; they con their way into being servants of the rich, only to realize it’s awful.

But the various introductions of, and desires to include, metaphors (the maid’s husband is living in the basement? He’s the literal definition of the underclass! Why that’s the literal definition of metaphor), make such a sensical transition impossible.

And so to the end, which also could have some weight to it, were it not for the inconvenience of wanting consistent characters. When the Rich Father (Sun-kyun Lee-ssi) mocks the Poor Father (Kang-ho Song-ssi) for the way he smells, we feel it, even if, and maybe even because, it’s a classic overheard conversation. ‘He smells like the metro.’ No one wants to hear that.

This works… if it wasn’t all the other movie that proceeded it. If he had been the trusted driver for many years, this would make some kind of profound character sense – this is what your boss, really thinks of you.

But Kang-ho Song-ssi had snuck his way into his role, and is shown not only materialist, but willing to kill (or, due to Joon-Ho Bong-ssi’s lack of familiarity with genre, maim) over it. If he was a Lackey Unleashed, his sudden burst of violence would have weight or empathy. As this is a Character For Every Situation, to serve as many metaphors as it can, the moment barely registers.

The film was always building towards this to be sure, but less by way of Pont du Gard and more by way of Chernobyl; catharsis this forced means we don’t care. It could have been a decent enough back and forth about the rich and the poor – in a time that so much needs it. Mr. Alexander Payne did a fair job with Downsizing, and Mr. Sydney Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? is the sinenonqua of the psychic sadism of class. It crushes the characters’ spirit, and yours too.

Both of these fellas ain’t poor themselves, so it can be done. If you care about story. Parasite instead preaches to the liberal arts educated audience – classical music contrasting the set visuals, shallow characterizations in elaborate metaphorical situations. Its job to engender the right amount of guilt: to make us feel good about how bad we feel.

And that, by the way, would be a Buñuel film.

I said early on, ‘If the dogs die, fuck this movie. ‘

The dogs didn’t die.

Fuck this movie.

The Take

-$15.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]