Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

A Bigger Audience

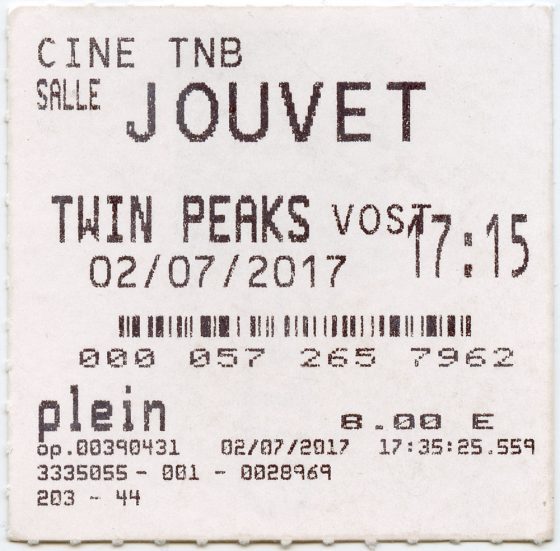

Being from 1992, I sadly do not have an original ticket to one my obvious favorites: Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. Thanks to France, now I do:

There are many things to recommend about this insane country, but certainly one is their willingness to see films in the theater. Though I dearly miss the experience, I have yet to actually see a film by myself here (that is, in an empty theater). You are grateful having not received a phone call during a 11:00a Thursday showing of Renaissances. It would be 2 in the morning for you, but I’m alone in the theater. That’s why I’m calling you.

It therefore heartened me to discover that the only screening of TP:FWw/M in Rennes – 5:15 on a Sunday – was half full. That’s about 120 people, which felt like the biggest audience the film ever got. The film is a mess, but contains, and this feels more objective than anything else, one of the top twenty film performances of all time (Ms. Sheryl Lee), and remains to my mind the best depiction of sexual abuse in any medium.

This was going to lead to a venn diagram, of messy, performance, and theme.

With subject headers like this:

Procrastination isn’t easy – it requires a lot of effort and access to Photoshop.

But then Bob is going to see it in two (now one) day(s), and so I have to write something to either help him enjoy it or prevent him from seeing it. The purpose of all film criticism. I wrote the following in a throwaway test of wordpress themes, and it sums it up nicely:

I would generally say that the heart, theme, story and writing of this movie comes from Ms. Sheryl Lee, without whom, there is really nothing. There is too much credit given to actors, and not enough to the right ones.

The more I think about the film and what works and what doesn’t, it comes down to Ms. Lee (and of course the man who plays her father Mr. Ray Wise).

What doesn’t work is largely down to Mr. David Lynch, who is happy to throw a gazelle up the parsimony and see who jitterbugs. Many things, the twenty minute opening, the actual murder, even Mr. David Bowie, do not engage in retro- or any other kind of spect.

Mr. Lynch’s scattershot approach did get one thing about sexual abuse very right (sic): the character of Bob, a set dresser who he accidentally saw through the viewfinder and thus lucked into one of the great and congruent gimmicks of all time.

Being fucked by your dad is not great. It further gives birth to the universe that is and yet also is not. The dreamworld of Mr. Lynch found a partner in this unnamable theme, a connection that conventional films have largely failed to do.

It’s genuinely odd that childhood sexual abuse, as big as it is in our imagination (again, sic), is so rarely depicted on screen. The second best example is possibly Chinatown, but only because it’s a great film. And let’s all accept that she’s my sister and my daughter is now less dramatic writing than future meme meat.

Films like The Lovely Bones and Prisoners and even A Cure for Life – absurd and sensationalistic – are not a little bit rapey themselves. Little Children and Happiness are fine, I suppose, but tend to focus, as we do so often, on the perpetrator. We’re obsessed about the topic, just not so much that we would want to talk about it.

Then along comes this dense, weird, indefensible little film, which has no equal. The character of Bob, captures the simultaneous disbelief and unreality of the horror – it can’t be dad, it has to be Bob. Even Mr. Wise seems to go along – I agree: it can’t be me.

The best moments in the film belong to Ms. Lee, without whom there is ultimately nothing. She is never a victim, and yet sad. Desiring and eschewing love in the same moment, she is horrible, and never less than sympathetic.

And then there is her performance, utterly ignored and yet hallmark now. She is the the embodiment of a tale told via her antithet, Ms. Jessica Chastain. Seemingly following Sir Lawrence Olivier’s advice to the letter, she does everything wrong. If she’s supposed to be kind, she bites. If she’s supposed to be afraid, she can’t stop giggling.

A Lynch/Lee conflict emerges in the final scenes of the film as Mr. Kyle MacLachlan comforts her in what is certainly not heaven, what with the angels flying around. It was a little unclear. She’s been raped and murdered by her father, but heaven!

And yet, there is Ms. Lee, first all beatific and accepting, and then, finally laughing hysterically, like the film and the universe aren’t so much beautiful as they are a cosmic joke, a last bit of rebellion from this disjointed and complete character.

The Lynch/Lee (and Wise) collaboration, on the other hand, finds its best expression in a memorable scene that should not be. If you’ve seen the film, you probably know what I’m going to say next: it’s where Ms. Lee and Mr. Wise are stuck at a stop sign and everyone – everyone – is yelling.

Watching it again, it seems a near Hitchcockian exercise in creating tension, a man with a walker crossing the street, then stumbling, the massive truck blocking the view, a man in an RV yelling at Mr. Wise, Ms. Lee asking, even though she knows: ‘Dad, are you all right?’ The film is able to let us see and experience the raw emotion without telling us what it’s doing. As Mr. Wise caps the scene and says: ‘When a man comes out of the blue like that, what’s the world coming to?’, it is a world with so much heartlessness, no one remembers the truth.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is, in honest reflection, not perfect or even great. It is not complete. There is a lot of junk, and some justified eye-rolling. It is a failed masterpiece. See it for the masterpiece. It’s there.

The Take

$14.00

Thoughts on Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

[logo]

[logo]

Lara Flynn Boyle?