Locke

I have become trailer, destroyer of films

I don’t want to ruin Locke for you, especially since we’re in the time vortex of 2014, where I’m getting Spiderman 2 before you, and you’re getting All You Need Is Kill after me, so don’t read further, since much will be discussed. It is good. You should see it. You will not be bored, which is why we pay money instead of just leading interesting lives. That’s not a judgement, except against me, since all I do is see movies.

Like all good films, I want to point out the strengths and weaknesses at the same time. Still reading? Yeah, you’re never going to see it, so let’s make a deal. I promise to not call attention to the fact you’re kidding yourselves, and I won’t look too closely at the fact that I don’t want you to stop.

So, the good:

It’s a beautiful exercise in negotiation, a man swimming in the admixture of concrete pouring, permits, bosses, affairs, and missed football games on a drive from Manchester to London. The fact that it takes place in a car actually makes it not feel like a play, the sense of movement like you’re always about to crash. And Mr. Hardy’s performance is so good should be appropriately ignored come awards season. No one likes subtle and inhabited and listening. When the time comes, think of it as an honor, Mr. Hardy.

But it’s the motive that works. Basically he throws away his marriage and his job all to be at the birth of his baby via a women he doesn’t love. It’s completely irrational, and yet ethical. In fact, the more irrational it becomes, the more we believe it. And then…

With the explanation of a man trying to deal with his Bad Father, it assumes, wrongly, that we wouldn't be sympathetic unless we knew he had a reason.

What the critics note, and they’re right, is the weak bit when he speaks to his father in the back seat of the car. This bothered me too, and I really struggled with it. On one hand, it immediately calls attention to the conceit of the film: that it takes place in a car, but it wanted more information that you would get in a flashback. It reminds you that it is a play, which one should avoid.

But that’s not why this clunky device, and it is that, fails the film. It’s because it explains him. I’ve used Hannibal Lecter before as an example, so let’s take a break from that and use Jamie Gumb. It’s a bit silly that he’s making a woman dress (though to be fair, the serial killer movie hadn’t been started yet, so novel and silly). What would have been extremely silly is explaining, as they do in the book, how Mommy made him that way.

And watching Aliens as I do every year, I just thought of another one. The point, that Ripley actually makes clear in the film, is that the spaceship that crashes on LB-426 is not from that planet. Neither is the Alien. What makes it cool among so many things, is that it has no origin. When they made the Abrams award winner Prometheus, they ignored not only this maxim (that not knowing something makes it all mythic), but were so desperate to create an origin story, they just smushed all these elements together, even though it was spelled in the film that Mr. Ridley Scott made that they were in no way related. We live in the time of explanation, that even the most minuscules of must be labored over for an audience that seemingly can’t stand a second of good ol’ fashioned (fashioned in the old way, that is) ambiguity.

Mr. Tom Hardy himself was an object lesson in this, having starred in The Dark Knight Returns as a character that was fairly compelling, at least until we knew he was born and was sad or something. Even wonder why the second is the best one? It’s because not only do we not know the origin story of the Joker (unlike the unfortunate Batman and the equally unfortunate The Killing Joke, and yes I just referred to a comic book), but the character makes fun of not telling the other characters Where He Came From, arising, like all great villains from the mist.

It seems like I’ve talked about this before, which never stopped me, but it occurs that the To De-Sabatier rule applies equally well to the protagonist. If they had left it alone, it would be the story of a man who destroys his life to be good. That’s solid on its own. With the explanation of a man trying to deal with his Bad Father, it assumes, wrongly, that we wouldn’t be sympathetic unless we knew he had a reason.

When it comes to what we know, it’s better to know the plot all in front, and let the motives be the surprise, instead of the other way around. I was put in mind of that great line from Glengarry Glen Ross, when it was just a play (that’s right, I used to read plays. Fine, play). This where Levene simply says ‘My daughter’ to explain everything that has gone on before. How much to we need to know beyond that? I like the film version, but the back and forth they added with Levine and the hospital spoils it. Locke is a lesson in what works, and almost all of it does, and what doesn’t, around the one pole of motivation. And since you’ve read this far, there’s no reason to see it, and you should.

The Take

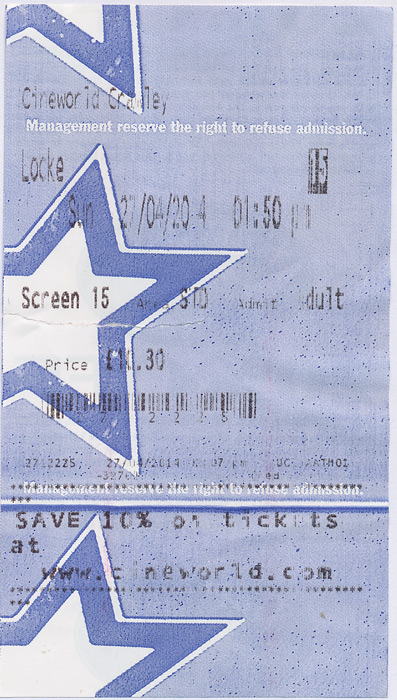

$12.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]