The Guard

The No-Rule Rule

Let’s say I wanted you to see a movie, in this case, a funny film called The Guard. I could spoil the jokes, but would that really you to get off your couch, or, alternatively, to get you to slightly move your cursor and download it (‘but the icon’s is all the way on the other side of the screen!’)? No, spoiling the jokes will just make you sit there and think that you’ve already seen it, so to motivate you to get up I’m going to spoil joking in general. Since there’s nothing less funny than talking about what’s funny, you’ll be compelled to do anything but continue reading, and this includes seeing the film. The fact that this relieves me of the duty to think of anything clever to say never occurred to me. Here my success is defined like that of truly great philosopher (which I also am, by the way, not a philosopher, a truly great philosopher). If you’ve got something new and challenging for the ages, you will be ignored in your own time. The fact the same reaction will be visited upon you if you are terrible or just mediocre should not deter you in any way; it doesn’t deter me. The one thing you don’t want is to be loved in your own time. Success, as a truly great philosopher might say, is for losers.

So onward to failure! I have mentioned before, but never explained, the John from Cincinatti v. Deadwood Rule. One show is indelibably great, the other, well, a baffling mess, and there is a very simple reason for that, or rather a reason on the subject of simplicity. You take a genre. You change one thing. You write. That’s it. If you take a genre and leave it alone, it’s dull. If you change more than one thing, the audience (and possibly yourself) will have nothing to hold onto to. In the case of Deadwood, take the western, and make it real (with naked people and swearing and the musical dialog of Mr. David Milch. That’s my definition of reality; you got a better one?).

Sadly, this talented fellow could not save himself from himself in John from Cincinnati, which started as Surf Noir (already one thing changed, so stop there), then added family drama plus mystical journey with Christ figure. There was no way to tell where anything was going or supposed to go, and without that, you get a baffling mess. Which normally I like, but in this case I didn’t. So it’s no so much a rule as it is something that sometimes applies, sometimes doesn’t, and without another rule to determine when it does or doesn’t. You make think it’s ridiculous to call it a rule, but I can see all the economists out there nodding their heads. They know what I’m talking about.

This is true of all movies, but especially comedy. Comedy is about inversion, about taking reality out of one person’s context and putting in another’s. This works as long as you know the context, which is why TV shows have it easy, except for the part about having to be talented, of course. They have time to create an environment and characters, and let the expectations be subverted from there. This is why good shows are often weak in the first few shows, but it’s also why when Jack Donaghy responds to Liz Lemon’s inquiry as to why he’s wearing a tuxedo, (‘It’s after 5 pm. What am I, farmer?’), it’s a great, great gag, but works even better by episode 7, because we finally know the characters.

In film you don’t have time to do this, so it’s helpful, nay wise, to rely on genre. The most successful comedies (i.e. the ones that are actually funny) place damaged one-dimensional characters in familiar situations: Lebowski is film noir, Quick Change is a caper movie, Groundhog Day science fiction (I like to see it as a remake of Source Code. Think about it: in order for this to be true, Mr. Bill Murray has the ability to travel in time), The Other Guys is a cop movie, and so on. This isn’t true of Ball of Fire, or Borat or Superbad, but you already know my stance on rules. What am I, an economist?

Because if we combine inversion and belief, we can imagine a final rule, the modern version of the the golden one: It all works as long as the rules apply to everyone but me.

In this environment, The Guard demonstrates this fact supremely well, as the film perks up measurably when Mr. Don Cheadle appears about ten minutes in as a foil to Mr. Brendan Gleeson. Suddenly we know what cops are supposed to do, and Mr. Brendan Gleeson takes inestimable delight in doing everything opposite, as do his bad guy counterparts. Comedy is about inversion, but it’s also about belief, the faith with which the characters invest their reality, and their confusion that they meet in other people’s response to it.

And so it is with The Guard, whose characters have absolute faith in themselves (this is a tribute, by the way, to both the writing and the acting). Bad guys are usually the funny characters in serious films, as they get to comment on social hypocrisy from the outside. I would say that in this case, Mr. John Michael McDonagh has inverted even this expectation, where the trio of villains is a bit more philosophical and sad. At one point Mr. Mark Strong is in an aquarium with his cohorts: ‘I like sharks’, he remarks at the end of the scene, ‘They’re soothing.’ I give away this line, largely because I like it, but also because it’s not so much funny as it a great example of the uncomplacent: We are waiting for him to say something sinister, and instead he says what the character actually believes. Everyone is themselves, and the characters do the unexpected congruently.

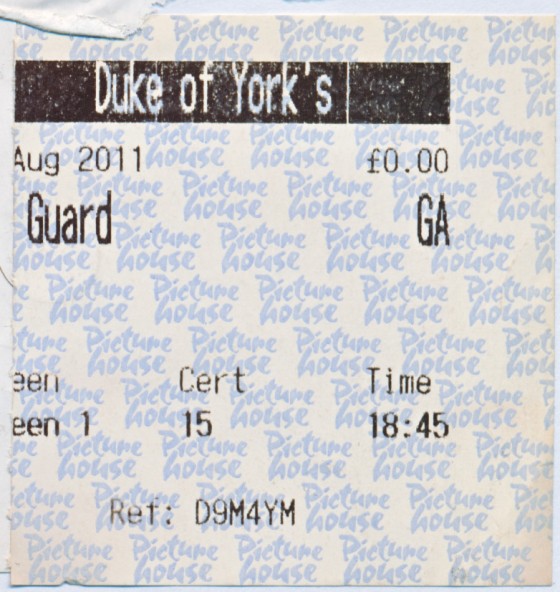

So I don’t give away any of the bits, I will instead cite a real life example that occurred at the screening itself. Waiting in the intolerably incompetent line at the Duke of York’s in Brighton (always get there 15 minutes early, as they don’t have a lot of trailers, and it takes about 2 minutes per customer to process the tickets. This is because people are always there buying tickets for another showing. Why they think they won’t have time to buy the tickets on the actual day of the show I’ll never know), I was treated to an impatient mother arguing that her children should be allowed into a 15 rated film (in the UK, it’s not like an ‘R’; kids just aren’t permitted, even with their parents to explain to them what the work ‘fuck’ means). She said, and I wrote it down, ‘No, you don’t understand. I just want to bring my children inside.’ It was her absolute belief in her own righteousness (combined with her utter lack of awareness that it was parents who wanted to protect their children who made the ratings system in the first place) that made this hysterical. Well, hysterical’s not quite the right word. In real life, it’s just depressing…hysterically depressing that is!

The Guard also contains a few choice bits called the joke double. Okay I made that up, and if I was in the comedian’s guild I’m sure that they’d tell me the real term, and then swear me to secrecy. So as a secret member of the comedian’s guild, which does not exist, there isn’t in any way something called the joke double.

It’s rare when you write something funny, but rarer still when instead of explaining the joke or having the straight man react, you then top it with another. The Simpsons (Seasons 5-6), was notorious for this, as when we see Homer Simpson coming upon his inexplicable exact double and then, instead of pausing to explain to the audience why this is funny (as they continue to do in The Simpsons post season 6, whatever wit that remained killed by a ricochet from the bullet that shot Mr. Burns), is suddenly distracted by a dog with a puffy tail. I love when this happens, because it both makes me laugh, and then it makes me go into the dull analysis of why I did. Also I have a dog with a puffy tail.

This film has one or two of these jokes; and so I won’t tell you what they are, let’s break it down. I could have said to the indignant woman, ‘I have an idea: you should start an organization that controls what children can and can’t see.’ Good, but this would be me playing the straight man. Instead, as God, I would have her say, ‘I’ll take three to the late show of Almodovar’s Cocksucker and Imploded Vagina Head.’ And mistaking the meaning of the cashier’s exasperated look as confusion, she would put away her £20 note, get out a £10 and a £5 and say, ‘Sorry, that’s one adult, two children’s tickets to…’

Am I the only one who wants me to be God? Yes, but I’m not the only one wants to be God.

If I was, I would put an asterisk by every stop and speed limit sign in the land: *Does Not Apply To You. Because if we combine inversion and belief, we can imagine a final rule, the modern version of the the golden one: It all works as long as the rules apply to everyone but me. The Guard is imperfect, messy even, but this is something that Mr. John Michael McDonagh seems to understand inherently. All funny characters believe in their own exemption, drug addled cops, self-entitled moms, sentient tires and even one or two disgruntled film bloggers. If they could see their ways through the absurdity of it, they’d be happy, but not funny. So let’s hope they never do.

$11.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]