Battleship

The Story of Alexander Fleming

Battleship is an important film, a sentence I feel strongly you will read nowhere else. You may hear it from the various Moms of those responsible, along with the adjectives ‘nice’, ‘interesting’, and ‘I disown forever; you are not my son’. But you won’t read it anywhere else.

Terrible, bloated and dull, but it reveals so much about what makes a story work, and what we seek in stories, that it becomes the petri dish where you wanted to grow mold, and wound up curing every disease in the world. That’s right: Battleship is that important. Or actually, I am, by proxy, for having noticed.

The big reveal on how to defeat the alien ships is…shoot them! Being in the military, this simply never occurred to the characters.

I have talked about the appetite for destruction before, what Freud very stupidly calls Thanatos and I very smartly call the Freud Was an Idiot Effect. FWIE basically means that we want destruction: White Houses blowing up and earths swallowed by nanobots and so forth. But this is only half the story, in the literal sense. We want destruction, sure, and then we want revenge, no doubt forgetting that it was us who wanted the destruction in the first place. In international relations, this is known as the security dilemma, where the building of great armies to protect yourself causes the other guy to build his armies so much bigger causing you to ask: why is my army so small? In the case of Battleship, the company responsible might ask, why is my logo so small?

Unlike mold, however, which at least is rather good at something like blue cheese, Battleship demonstrates baffling incompetence on even the most basic logic for character’s behavior. For a person obsessed with structure, it was a mind-bending experience. Let me give you an example. The film spends a great deal of time establishing the aliens point of view, with the various ‘aliencam’ that we’ve see in many films before (though strangely, after having seen the aliencam, we are told that they are blind. Moving on). In this case, it serves as the explanation for the aliens blowing some stuff up, and not others. Sometimes the aliencam flashes green, and does nothing, sometimes red and blamo, or giant spinning spike-o and so on.

Okay, fine. All my ticket stubs from England are in France, so I used this year old picture of a standee for a review of a six month old film. Sue me for all the money you paid me to read this.

Now the whole time my brain is working overtime to discover the logic behind these seemingly inexplicable choices – are they really peaceful and reacting to a threat (see security dilemma above)? Are they time-travellers from a better film about time travel? Is it totally fucking random? It was only at the end of the film that it was revealed that the aliencam was actually some sort of live connection to the dial of the focus group watching it months ago (or, as is often the case, the day before it came out). The physics of how this happens would be a subject of the better film about time travel, but how else to explain the aliencam’s bizarre choices? When the alien blade ball encounters a child, it flashes green – the audience doesn’t want to see that, and the blade ball moves on. When the alien blade ball encounters a freeway: red – focus group says must destroy! What’s that now? Freeway overpasses have cars full of children?

Yes, but we don’t have to see them, do we?

Unfortunately, the red/green effect applies to the alien’s (and the human’s logic). Sometimes they blow stuff up, sometimes they don’t. The big reveal on how to defeat the alien ships is…shoot them! No, really. Being in the military, this simply never occurred to the characters. Which gets us back to mold somehow, or at least to me being Dr. Alexander Fleming, since it answers: what do we want in story (and possibly in international relations)?

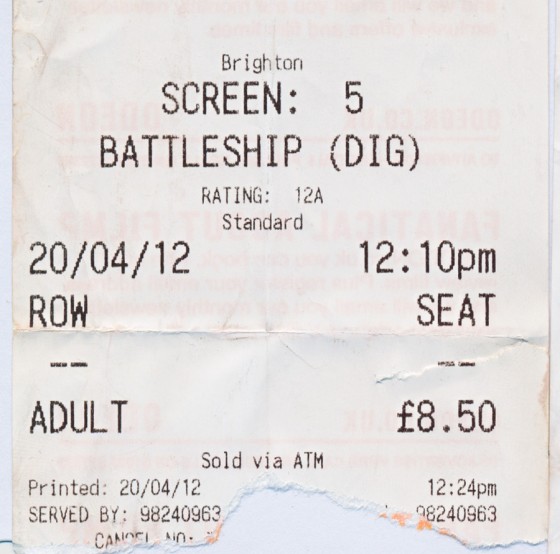

Nevermind. Found it. You owe me all the money that I refunded you. You know, that you paid to read this.

The amazing thing about Battleship is that the characters (alien and human alike) simply wait for this to happen, asking the audience to go along. Which we do.

This type of film is mirrored exactly in our poorly developed and unrealistically motivated character’s ‘arc’ (a term as detestable as ‘blog’, to be sure), used to signify when said personage changes. Now I’m not one of those guys who says people changing isn’t realistic, and even if I was, this a film with aliens based on a board game. You have to pick your battles. No, change has its place in story, but here is it purely mechanical, as indicated in the dialog, and I quote: ‘We need you!’ ‘I can’t!…and now I’ve decided I can!’ Well, quote the film for the first part and myself for the second. This is the arc: I’m afraid of responsibility! Now I’m not! Exclamation points emphasize the significance of change!

Let’s take the game, which the film resembles in no way except in one scene. The bit is this: the guy is shooting at a point on the grid, trying to anticipate where the ships will be. Having never played the original game, a video game, or without even the very basic knowledge of objects moving in space, our character simply waits for the blip to appear, then pauses for no particular reason (technically speaking he’s waiting to create tension, see above), then authoritatively intones ‘Fire!’, misses three times, then hits and everyone cheers. Unlike the most basic story, board or video game, there is no sense of space, time, or rules.

Now there’s really nothing wrong with this type of storytelling. It functions as it is supposed to. The filmmakers jam the characters into a situation, telling us what is happening, then jam them out of it. Accordingly, we feel emotion, which is why we paid money in the first place; it’s not like we feel any emotion in real life. Nor am I one of those idiots who says that it was better back then, as anyone who says they have seen the incredibly popular, and completely unwatchable, Andy Hardy Singlehanded Destroys The Narrative films will attest.

The ultimate problem is repeatability. Stories without logic are fine; they’re even entertaining. But they will never be something that you can watch again, because without the act of characters making relatively intelligent choices, there’s no tension. This is why when SotL or Aliens or Justified or Miller’s Crossing suddenly crops up on TV, you say, just a couple minutes, and wind up watching the whole thing. The Deus Ex Machina model is fine, and it works. Once. And who, in the future wake of astonishing opening day grosses, and equally astonishing second week drop offs, would want to make a movie that you can only see once? Poorly developed and unrealistically motivated movie executives. If only they were written better.

The Take

$2.00

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]