SotL

This Only Exists For Another Post, Which I Have Yet To Write

Was asked by my friend Bob why Silence of the Lambs works so well as narrative. In ten minutes I tossed the following few paragraphs off, referring to them often. Which is strange, since all the other writing I do is arduous, and requires referring to rules. Writing about rules is quick, and requires referring to writing.

I’ve often asked myself that same question, and I will preface the following with the caveat that if you’re doing SUTLM, many of these will not apply:

Jeopardy: This is pretty straightforward, but a lot of movies forget to do it until it’s too late (see Surrogates, X-Men, etc.). Take a likable character, put him/her in trouble. Do it right away. This can also go under the heading: start at the best place, not at the beginning. We don’t need to ‘know’ anything about these characters that the story won’t eventually reveal (imagine if the lambs screaming reveal came at the beginning, as it would with so many films. Blech). In the case of SotL, I’m not talking about Catherine (who is kidnapped 25 minutes in), but Clarice, whose sanity and future career are put on the line immediately, in the first two minutes.

My jokes are so desperately random, like the elaborations of a bad flyer.

Instrumentality: The goals are legible, that is to say, X is located in Y, which Z needs to do A. This is why sports work so well: there’s a score. Hannibal is located on the fifth floor of the court house. How is he going to get down? With a penclip. Jaime Gumb is going to kill Catherine. How long have we got? Clarice must graduate (and survive). Etc. Everyone’s desires can be fulfilled by a goal which we can see: ‘save the girl’, ‘kill the girl’, ‘escape’ (applies to both Catherine and Hannibal). The goals are not vague like ‘feel better about myself’ or ‘my mom loves me now’. This rule actually does apply to comedy (‘kiss the girl’ instead of ‘become the kind of person that’s attractive to girls’: vague.) This even applies to Gumb’s motivation for killing: he’s making a woman suit, so even his pathology is instrumental. The film is a map, and we always know where we are.

Knowledge: This is not a shitty Agatha Christie mystery (could it be that Cary Elwes is the killer. No! Then, Yes! Then, who cares!). We know, right away, that Jaime Gumb is our guy. Very few writers do this because it is much easier to maintain tension by simply withholding information from the audience. Not that SotL doesn’t do that, but it’s always about why rather than who, how rather than what. This leads to a particular risk when the audience knows more than the characters, but the characters are smarter than the audience. But this leads to a more Eureka style like all great ideas (say Facebook). When these ideas arise (he’s making a dress out of women, etc.), they seem familiar, as if we could have thought of them, but didn’t. Which leads us to the most important rule:

Competence: None of the characters behave like idiots for convenience of the plot. Everyone is smart, and good at their job. There is no artificial conflict (as with Hannibal) between the ‘suits’ and the ‘grunts’. The lieutenant and the cop who doesn’t play by the rules. So boring. The feeling of the film is that of a chess master playing himself. The way Hannibal is kept is smart, how he gets out is smarter. Crawford knows Hannibal, sends Clarice instead. Hannibal knows Gumb, keeps it to himself, etc. Even Catherine tricks Precious into coming down into the hole with her. Everyone thinks. The interesting, and very smart, exception to this rule is Clarice, who is allowed to be vulnerable (as when she cries about her father), but never lets her vulnerability get in the way of her job.

Research: These are for the details above. Moths, orphanages, psychopathogies, prison cells, the view from the Hotel Belvedere, sewing. Each area of expertise is a view into a new world for the audience, as well as an arena for the character’s competence to shine. Weirdly, this also works for comedy as the complete universe exists for each character (and their absolute belief in it) is what works in comedy: clashing realities.

That’s all I can think of for now. Must finish piece on Rubber. It’s about girls.

—-

Editor’s note, March 2016 – Saw it again, as I do, and here’s one other:

Compression: I’ve been thinking a lot about this since Mistress America, and there is a sequence that demonstrates everything you need to know how on to make a good film. At the end of Lecter’s escape, there are three shots: the body in the elevator falls through the door, Lecter gets up in the ambulance and pulls off the face from the guy in the elevator, and a telephone off the hook, with Ardelia’s running feet.

Here’s what’s not shown, what any other film would have: the guy’s face in the elevator, what Lecter does, and Ardelia’s face. The film lets us fill in the gaps (which it does so often) and there is a lot between the tape.

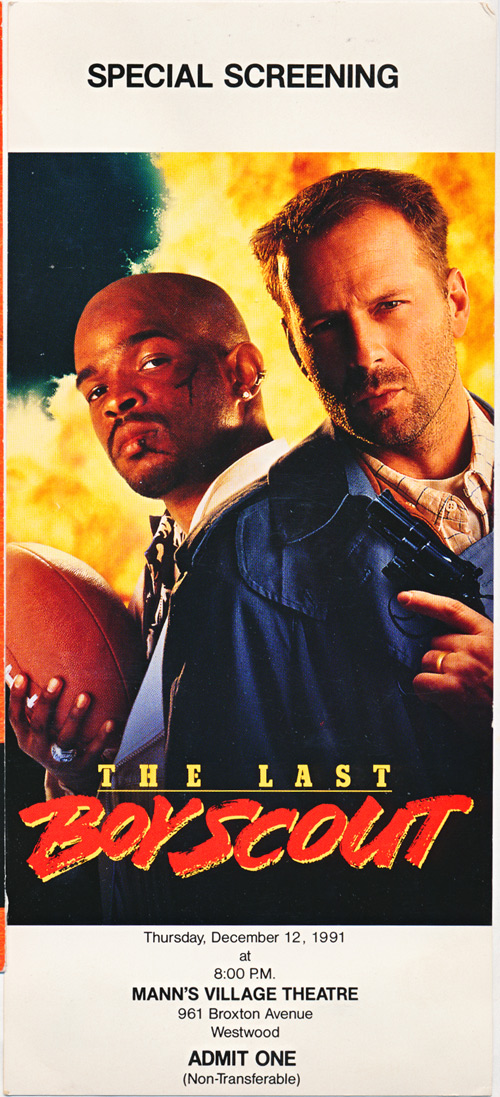

$241.00

Editor’s Note: Though the above is not the actual ticket from SotL, as it came out before I started collecting tickets in 1994, I include it as I saw the film at a sneak preview. This served as my introduction to filmgoing in Los Angeles. No wonder I stayed for 20 years. Also, no wonder I keep thinking films can be good.

Sadly I do not have the original ticket, so I used the most proximal sneak preview one, age-wise. This was, naturally enough, The Three Musketeers. I would normally follow a mention of The Three Musketeers by something along the lines of ‘you know, the good one’, but I’ve long since lost count. There were more than three, I know that.

But if using a generic substitute sneak preview ticket, I could have just as easily used this one:

Or this one:

This one would be harder to sell as SotL, but at this point we can agree that I’m just showing off.

Other sneaks have included Kuffs, Clear and Present Danger, K-19: The Widowmaker and The Usual Suspects. At this point, we can agree that I’ve gone beyond showing off, and am just great.

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]