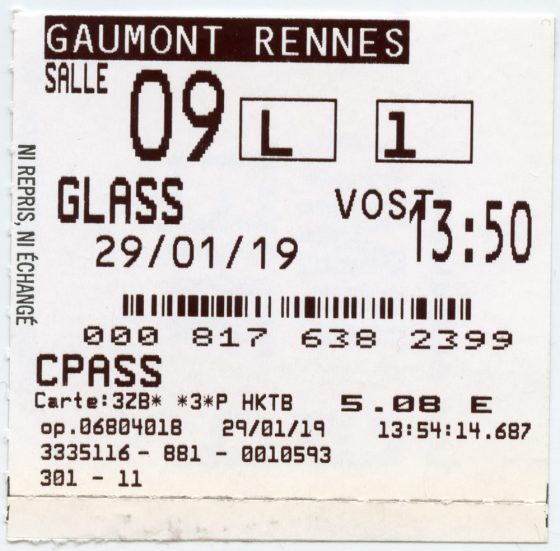

Glass

Going Sub-zero Turkey

(Editor’s note – well the site has been dark for a few months. A combination of three things – one, lack of anything to write about. Oh, I’ve been seeing films in the worst year of cinema history, but they have failed by and large to rise to the visible. I’d happily see something commendable, but I’ll settle for commentable. Two, I’m writing furiously to have a (second) script for SXSW in the vain hope it will pay me as much as this does. And three, you know when you’re trying to lose weight, and when you just lose a little, you tell yourself, well, now I can eat whatever I want? When I got my ten year chip, no doubt I felt like, well, I did a blog for ten years. Now I never have to write again.

If only that were true.)

Glass is ten minutes better than Split. It is unfortunate that these minutes are the first ten. Within, the already established Reluctant Superhero from Unbreakable (Mr. Bruce Willis) pursues Mr. James McAvoy’s multiple personality serial killer from Split. It works because we know the terrain, and further so because his son (Mr. Spencer Treat Clark from the original) is helping his father in his fight against crime. It’s a potentially moving relationship, uselessly squandered.

Mr. Willis finds Mr. McAvoy, rather too soon, and both are captured instantaneously, a set-up for an contest-winningly slow twist reveal. One could have had the events play out, say the cops pursue Mr. Willis who pursues Mr. McAvoy as Mr. Samuel Jackson plots in the background. Lot of nice chess pieces on a well-defined board.

Instead, there is talking.

See even though we, as the audience know that both Mr. McAvoy and Mr. Willis have special powers, Ms. Sarah Paulson has to try – for the next ninety minutes – to convince them that it’s all in their head. Really. That’s the story. It is the dramatic equivalent of watching someone tell Mr. Neil Armstong the moon landing was a fake. Sans the satisfaction of getting to punch him in the face at the end.

This goes on. There are scenes of the characters individually. There’s the scene where they’re all together for the poster, even if it makes no sense from either a story point of view or a lack of story…point of view. There’s individual scenes identical from the previous two films, all say the same thing: you’re just deluded. You’re not special. I suppose endless repetitious dialog like this could relate to someone who was once told they were magical, and then was told they’re not, and is trying to convince the outside world of this fact by saying over and over and over. To an audience, however, it is as tedious as my repeating it here.

After – really – ninety minutes of this (with some establishment of the fact that the premier high-security psychiatric hospital in Philadelphia has two guards. That’s total, by the way. One at a time. No, I’m not kidding. Only a super genius could escape!), the twist arrives: Ms. Sarah Paulson is in charge of an evil organization that’s finds and kills extraordinary people. The whole spiel was a test to see if the three, again that we know have super-powers and have known for 18 years, were just faking.

Should have said spoiler alert. But with something this rotten…

This kind of enemy of dreams is a standard fare pablum villain. No objection. Children need to be told ‘you can do anything if you dream’. This is so that 99.9% of us can be filled with self-loathing when we fail and the remaining 0.1% can convince themselves that their random unwarranted luck was ‘success’. It is the way of the world.

Ms. Paulson is trying to determine if those people are special and, if they are, kill them. She needs evidence. This makes even less sense given that the twist on the twist is that it was Mr. Samuel Jackson’s Plan All Along to film them to Show The World There Are Extraordinary People. Dream, Audience. It makes you into better slaves. See above.

Now we could critique this from a logic point of view, that either one – in the intervening eighteen years – could have hired someone to follow Mr. Willis around with a video camera. Mr. Jackson instead cleverly waits in a mental institution so that Ms. Paulson and her suspiciously tattooed goons kill them. We’ll get to the the ugly ending by way of Mr. Billy Wilder and Mr. William Goldman.

In the meantime, Glass falls irredeemably flat because there’s no reason to keep this a surprise from the audience. Why not, with all those elegant pieces on the board, know this from the beginning? It’s about getting evidence, and one character wants to destroy it, the other to show the world. Extremely basic and satisfying genre.

The de facto solution – surprise – is both neurotic and lazy. Lazy because as I mentioned, I’m writing right now. Writing is hard. You have characters who want things. Those desires conflict. But how do you work out say, the mechanics of them meeting each other? What do they know? How do they know it? How do you let the audience know what’s going on without sounding like a chump?

In another film, a scene like this would be moving. In this film, you just cry.

Surprise solves a lot of these problems – hide it all from the audience. Mr. M. Night Shyamalan might be the Ricky Ross to our own current addiction to surprise, but he also got high on his own supply. In his defense, Mr. Shyamalan comes about his addiction honestly, or at least neurotically (part 2 of ‘neurotic and lazy’). It’s the lucky charm he keeps rubbing so the rains will come again.

And surprise can work, as his two first films attest. The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable do so because the character is on the same journey as the audience – to discover the secret. As the need grows to fool the audience, the machinations become ever more arcane, as we have in Glass.

The surprise habit leads to the extremely unpleasant scene wherein a nameless faceless cop with the tattoo drowns Mr. Bruce Willis in a shallow puddle, while his son watches twenty feet away, presumably…not filming? Not helping? But I kept him off-screen! That’s the same as his not being there and interfering with the ending I so cleverly planned.

The clumsy staging of this scene is glaring because of Mr. Shyamalan’s desperation to show us The Blackness Of It All. But it’s not dark or meaningful. It’s just shitty.

Why shitty? I was put in mind of Mr. Billy Wilder’s near masterpiece Ace in the Hole, a rare misfire box-office and critic-wise for a peculiar reason. Now, an actual spoiler alert, because this is a good film. See Ace in the Hole, come back. Or pinky-swear you’re never going to. Because who sees films anyway.

Quoting from Mr. Gene Phillip’s biography.

But (Wilder) realized in retrospect that, when a director stages an incident of this kind—in which a character’s life hangs in the balance—usually the audience implicitly assumes that he will show the helpless person being saved in the nick of time, thereby releasing the tension that has built up in the audience. Consequently, the audience feels cheated if the threatened peril actually overtakes the innocent party and they are denied the satisfaction of seeing the individual emerge unharmed…Wilder reflected that portraying this sympathetic man perishing in such a dreadful fashion was a cardinal sin.

Ace in the Hole, nevertheless, was secretly one of Mr. Wilder’s favorites and for good reason. The innocent man dies, yes. But he does so because of the schemes of Mr. Kirk Douglas, who thwarts the rescue attempts via blackmail, praise and threats, all to prolong the peril to sell more newspapers. His schemes embody our desire for drama, and our willingness to look the other way as to how the sausage is made. We feel the loss, and our part in making it happen, and it matters.

But killing an innocent character is a risk; in Adventures in the Screen Trade, Mr. William Goldman noted the dire audience reaction when he failed to follow this principle in The Great Waldo Pepper. This sin needs a reason (like a sacrifice for other characters), or a villain vanquished (Michael Clayton does this to powerful effect).

What it does not need an anti-climax, an ending where we are shown things we have already seen, and learn things we already knew. You wait, vainly, for the hoped yet deliberately denied twist that that Mr. Bruce Willis lives, that surely no filmmaker is that disconnected from how an audience experiences a film to think that being shitty constitutes surprise. Like the silly mislead at the end (see below), being bad at your job is now the ultimate gotcha.

Glass instead leaves a bad taste in your mouth, sans the satisfaction of punching someone that just told you that this is just how we make films these days.

The Take

-$24.50

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]