Doubt

The Logic of Better-Than-Averageness

Dietrich Dörner, in The Logic of Failure, outlines the various ways systems, countries, nuclear safety teams, and minor bureaucrats create disasters, all the while knowing better.

And, for a change of pace, I’m not going to apply this to studio heads, but to myself. It seems there’s a particular way that we do, that I do, stupid stuff, and that is called Goal Degeneration. Basically, if you start out trying to run a nuclear power plant, become consumed with how good you are at running that plant, you might try to prove how smart you are and cause a meltdown. It’s mistaking the means for the ends, and it’s something we do all the time: if you get into a relationship to be happy, and wind up fighting all the time for the sake of the relationship, that’s goal degeneration.

A few months ago, as a goof, I started writing a little bit about movies that I had seen. It was fun, trying to be witty, and sometimes succeeding, and putting it down on paper, or, for the more literal minded, on MySQL servers. Sorry that’s my MySQL servers. Then, it became something I had to do, and it wasn’t so much a goof anymore. Then, I saw Doubt, and it reached the threshold, what we’ll call the homework continuum. The goal, of goofing off, had degenerated into something obligatory. So to get back on track, and not cause any Chernobyls, from a literary point of view, I’m just going to ramble, and see what comes of it.

What it was not called was Ouch: There’s a Priest Fucking Me in the Ass.

[/pullquoteR]Doubt presents its a problem right away: a movie that I should have liked, but didn’t. It’s a perfect companion piece to Frost/Nixon, since it’s got high quality writing and the damaged specific characters I talked about. Sister Aloysius is the perfect unlikely hero: angry, conservative, rigid, and yet the only one willing to stand up to the cheerful child molesting priest Father Brendan. Viola Davis, who’s always been pretty good, is getting a lot of attention not so much for the performance, as the combination of the performance and scene, where a mother chooses to have her boy in the presence of a child molester so that he could survive school. You’ve got a lot of great scenes, choices made, consequences doled out, clever and naturally realized situations. And yet…

I think my problem is with the title. And while many a weak title has diminished a great film (Once pops to mind, as does A Simple Plan), that’s not what I’m talking about here. Doubt refers to a the intellectual concern of all the characters, and reveals very much the interest and intention of the writer and director: a debate about faith, God, consequences and choice. What it was not called was Ouch: There’s a Priest Fucking Me in the Ass.

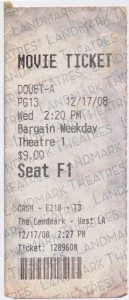

I paid cash, so the ticket would look better than the one that comes out of the credit card machine. I did it for you, gentle reader.

And if that’s offensive, good. At the center of the story is a boy being hurt. As all the various characters debate as to what’s true, what’s effective and what’s fair, he’s being left by the wayside. I would even argue that the filmmakers are aware of this; that the film knows the characters are more concerned about what’s right than the person being hurt by what’s wrong. But that’s a cop-out too; I think that it’s scary to probe that kind of pain, and I would accuse the filmmakers of taking the coward’s way out. In the very brief moment where we see the boy weep as Father Brendan leaves the Parish, we know this is a complex and deeply sad character. I wanted to know more. I’m not going to debate what’s right or wrong to depict on screen, just what’s interesting, and, in this case, what allows us to identify to a onscreen character.

What Frost/Nixon had, and this film seems to lack, is vulnerability, a soft place for us to connect. Nixon is that exposed little boy, and, in Doubt, that little boy is a mere reference point. The characters are all interesting: the source of reform and kindness who is a child raper, the savior a traditional nun, the mother left to choose between two impossible outcomes. But what about the character of the film? It seems to be missing, or afraid to come out.

I’m not so stupid that I think a good movie for me is a good movie for everyone, that we’re all seeking the same thing. But I also know, or at least I do now, that I need to see the raw heart of a character, or in the movie itself, to bring me in. And I would call Doubt a failure on that account: that we never see the soul of the writer in there. And we need to. At least I do. Whatever this commentary started out as, it seems I’m trying to find out what makes a movie work and what makes a movie falter. And in the tradition of coming out, I’ll say this: I suspect that I’m doing this because I’m gearing up to write again, despite the past failures and rejections. Which is all the vulnerability you’re going to wring out of me for now.

Profits!

Losses!

$3.50

The Lonely Comments Section

[logo]

[logo]